What’s The Story, Muthur?

To the point, tabletop gaming

Popular Posts

The Five Variables of a Core Dice Mechanic That Matter

A core dice roll is a bundle of variables that shape how a game feels, how players assess risk, and how much work the GM has to do. This post breaks down the five big factors inside the dice loop: who sets the target, what shape the randomness takes, how odds get modified, how outcomes are interpreted, and when you should actually roll in the first place. Each of these choices changes tension, pacing, tone, and player responsibility.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap

TL;DR:

A core dice roll is a bundle of variables that shape how a game feels, how players assess risk, and how much work the GM has to do. This post breaks down the five big factors inside the dice loop: who sets the target, what shape the randomness takes, how odds get modified, how outcomes are interpreted, and when you should actually roll in the first place. Each of these choices changes tension, pacing, tone, and player responsibility.

Introduction

Last time we talked about what a core dice mechanic is, so today we’re going to dive into the five variable elements of a dice loop to dissect what happens between the expression of player’s intent and the result, and then why so many systems seemingly reinvent it.

Get yourself a cup of tea for this one, there’s a lot to unpack here.

The Dice Loop

Quick refresher first for those at the back: what do I mean when I talk about dice loops? Well, I’m talking about the four stage process that happens whenever you engage in the core mechanic. Specifically:

1. Action declared

2. Variables Applied

3. Dice Rolled

4. Consequences Interpreted

This post drills into everything that happens between declaring the action and reading the outcome. That is the variables that shape odds, difficulty, and tone.

Variable 1 - What Are We Rolling Against, And Who Decides?

Whether you call it the DC, TN, AC, or number of successes, this variable is simply the target you need to beat. Different systems decide that target in different ways, and that choice carries a lot of weight.

Some games put the decision in the GM’s hands. In 5e, for example, the GM sets the DC, which gives them fine control over difficulty but also creates a subtle conflict of interest to manage: you want the players to succeed, but you also want the challenge to feel meaningful. On top of that, every judgement call adds to the GM’s mental load, which is already stretched thin.

Other systems remove that burden entirely. In GOZR, for instance, the GM doesn’t set a difficulty at all — the “target” is simply the relevant character stat. That strips out GM bias and keeps the load light, but also means the GM can’t tune difficulty moment to moment.

Therefore this choice changes the feel of the game. Rolling against fixed values gives players more meta-knowledge and puts responsibility for risk firmly in their hands, encouraging calculated decision-making. However, when the GM sets the target instead, players may feel the GM shares responsibility for success or failure — which is why you often hear GMs say things like “I killed my player last session.”

Variable 2 - What Shape Does Randomness Take?

You can also radically impact the game by what the game has you roll, due to the way different combinations of dice affect results distributions.

Single Dice

A single dice, take a d20 for instance, has a 5% chance of landing on any given result. For this reason, single dice rolls can feel swingy as the range of possible outcomes is equally likely. This is part of why 5e feels “heroic” - massive rolls are not uncommon in comparison to other results, and there’s a good chance of getting a stunningly high roll at any given time. In isolation it also contributes to comedy goofy moments where massive failure is also a very realistic prospect.

Multiple Dice

However, if you roll multiple dice and combine the score, then you’re in a bell curve distribution situation where the final result will heavily favour the median possible outcome, and outcomes at the extreme success and failure ends will be significantly rarer. This has the effect of making the game more predictable, and therefore gives the player more ownership over the outcomes they generated. It works well for games with high lethality because players can predict odds more reliably:

2d6 result | Odds

2 or 12 | 3%

3 or 11 | 6%

4 or 10 | 8%

5 or 9 | 11%

6 or 8 | 14%

7 | 17%

Dice Pool

If you have a dice pool system, like in AlienRPG where each result of 6 is a success, in that circumstance each dice added to the pool increases your chance of obtaining at least one success, but the impact on the odds that each new dice added to your pool shrinks massively with each new dice added via diminishing returns:

Dice | Odds | Increase

1d6 | 17% | +17%

2d6 | 31% | +14%

3d6 | 42% | +11%

4d6 | 52% | +10%

5d6 | 60% | +8%

6d6 | 67% | +7%

7d6 | 72% | +5%

8d6 | 76% | +4%

This type of system is good for capping the ability of player characters within a certain range, keeping abilities grounded which is important for systems where you want your players to never feel invulnerable.

It’s undoubtedly true that rolling big handfuls of dice is not only fun, but also that fraction of a second you spend sorting through the results hoping for a success is tense.

Variable 3 - How Do We Modify The Odds?

This works very closely with variable 2, because different dice methods of generating RNG present us with different options for modifying those rolls.

Additive Modifiers

A common method to change the odds of a roll is to use your character’s derived stats and “add your modifiers” to the result of the roll. This is clean and intuitive from a simplicity standpoint, but in doing so, it takes certain low results off the table completely. For example, a 5e Rogue with a +9 in stealth is never going to score less than 10 on their roll (we’ll talk about critical fails in a bit) and that’s a problem, because now our modifiers have moved beyond adjusting the odds toward creating certainty and in doing so risks undermining the purpose behind having a core dice mechanic in the first place.

If you want to create a game where the players can indulge in a power fantasy, this is the route to take.

Dice Chains/Step Dice

Rather than giving players a bonus of an absolute value to add to their dice roll, dice chains and step dice elect to give them a different sized dice instead. Let’s assume that you want to roll high - in this case, a character rolling a d6 is capped out at 6, vs. a character rolling a d12 is capped out at 12.

The potential of the d12 character is therefore twice that of the d6 character, but we’ve avoided creating certainty, as a d12 can still roll low. So instead of narrowing the result range as with additive modifiers, step dice grow or shrink the entire results band upward or downward.

This works well where we want to give players meaningful variances in ability without turning their characters into unbeatable demi-gods, but it does make dice rolls slightly less intuitive. Who hasn’t had that player that asks every time about what dice they need to roll, even when it’s always a d20? This will probably exacerbate that problem!

Advantage/Disadvantage

Advantage/disadvantage is one of the simplest difficulty tools you can give a GM: roll twice, keep the better or worse result. It shows up in different forms across systems, but the core idea is always the same.

There’s a lot to like about it:

It’s clean. No maths, no modifiers, no lookup tables.

It’s emotional. Players immediately feel the stakes when the dice leave their hand a second time.

It’s universal. You can bolt it onto almost any core mechanic without breaking anything — d20, roll-under, step dice, dice pools, whatever.

But it’s not flawless.

Firstly, the maths isn’t intuitive. Rolling twice feels like a small nudge, but in a d20 system advantage is worth roughly a +3 to +5 bonus depending on the situation which can be bigger than many GMs intend. The reverse is true too. If you don’t know the underlying probability shift, you may end up modifying odds more aggressively than you realise.

Secondly, it adds friction. You’re doubling the number of rolls, and while that sounds trivial, groups who rely on this mechanic heavily might notice the slowdown, especially at tables where players already hesitate or re-check dice.

For those reasons, the only time I’d avoid using advantage/disadvantage is when the system already has too many levers to pull. If you’ve got static modifiers, step dice, DC adjustments, and situational tags all competing for attention, adding another knob to twist just dumps more cognitive load onto the GM and makes it harder to stay consistent.

Variable 4 - How Do We Measure Outcomes?

Binary

Essentially we have three options. Firstly, we could argue that it is purely binary - the roll resulted in either a success or failure. This is clean and simple for sure, but it does not lend itself well to interesting outcomes, or keeping the game moving forwards. We’ve all heard the advice that as a GM, you should try to avoid saying “no”, well that’s what a failure is in this circumstance - it’s “no”. The problem is that it’s shut down an avenue of progress without opening up an alternative.

On the plus side though, it’s light on GM load. There’s nothing difficult about interpreting a binary result, and it’s clean and fast, and there’s less chance of the players feeling like they’ve been victims to some unanticipated gotcha.

GM Fiat

The second option creates GM load in the extreme, and opens you right up to conflict of interest: There is no codified success or failure - the GM simply interprets the strength of the result and assigns a suitable outcome to it based upon fiat, circumstance, and vibes.

GM fiat isn’t an official mechanic, but it becomes a de facto one when rules don’t specify degrees of success - you’ve seen it in action when the GM calls for a roll, you score a 4 and everyone at the table understands intrinsically that you’ve failed, yet the GM sort of awkwardly goes on to award you a success of sorts because failure wouldn’t have made sense.

It’s only really an option for non dice pool mechanics though. No one would be able to get away with witnessing a dice pool result of zero successes and then contorting that into a limited success!

Degrees of Success

This option is a middle ground. In this system the game has some codified way of defining outcomes more than yes or no. Typically opening up to:

yes and

yes

yes but

no but

no

no and

Now different mechanics will allow this in different ways. With a dice pool, it might be that you strengthen the outcome with the more successes you roll. With other systems they break possible dice results down into ranges, either according to absolute values (such as 1 below TN) or percentages (such as 10% below TN) and then transpose the list above to those ranges.

We’ve seen this applied to great effect in games like Call of Cthulhu where the ranges regular, hard, and extreme are mapped to a percentage over or under your stat, or Powered by the Apocalypse, which favours absolute values.

Critical Hits

Critical hits are a wildcard baked into many core mechanics; that sudden spike of drama when the dice explode, double, or land on that one special result. In design terms, crits are a way to break the expected curve, injecting moments of swinginess into systems that might otherwise feel predictable.

The simplest form is the classic natural 20 in D&D: roll the highest face on the die and you get a bigger, flashier result. What’s important is that this happens regardless of modifiers. Even a clumsy novice can occasionally land a perfect blow, and even an expert can fumble catastrophically. Crits flatten the power curve in tiny unexpected moments, and as a consequence they’re exciting.

Different systems spin this idea in different ways, and they tell you what sort of game you’re playing:

Linear dice systems (like d20 games) produce crits fairly often because all outcomes are equally likely. This reinforces the “heroic swinginess” the d20 is known for.

Bell-curve systems (like 2d6 or 3d6) make crits rare and meaningful, because the extreme ends of the curve hardly ever come up. You’ll still occasionally roll a double six or triple six, but it’s much rarer and less reliable.

Dice pool systems handle crits by counting multiple successes, matching numbers, or converting high results into special effects. This lets crits scale with character competence: more dice rolled equals more chances to spike, but still without guaranteeing it.

Exploding dice create a different flavour of critical entirely: every max roll triggers another roll, allowing theoretically infinite results. I use them when I play D&D because it kind of represents the lowly peasant hitting the dragon in his eye with an arrow.

Under the hood, critical hits interrupt the normal flow of risk and reward. They’re a “spike of possibility” that keeps players hoping, even when the odds aren’t in their favour.

Variable 5 - What Justifies A Roll?

Of all the variables in the dice loop, this one is the most misunderstood: when should you roll at all? It sounds trivial — “roll when there’s uncertainty” — but in practice, this decision shapes the entire pace, tone, and feel of a system far more than most people realise.

I’ve written about this before in my older post (Do You Call For Too Many Rolls?), but it’s worth pulling back into this series, because it turtley belongs on the list of core variables.

A game that rolls sparingly feels empowering, deliberate, investigative, even cinematic.

A game that rolls constantly feels random, procedural, or punishing.

A game that leaves it vague risks becoming muddled, inconsistent, and exhausting for the GM.

Conclusion

Well done, you got to the end! Honestly that one was a lot of work and took ages to write up, so I hope it proves useful to all the TTRPG dice nerds, academics, and designers out there. If you didn’t catch the first post in this series, you can check it out here, and stay tuned for the next piece on what mechanics work well with different tones and genres.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running!

Catch you laters, alligators.

What’s in a Core Dice Mechanic?

I’ve been asked to review a lot of systems lately, and I’ve noticed myself drawn immediately to an analysis of the core mechanic of the game in question. Long may this continue, but wouldn’t it be helpful, thought I, if there was some well thought out way for me to sort and identify techniques, using common language and a clearly developed pitch regarding what does what well?

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap

TL;DR:

Every tabletop RPG needs a way to decide if an action succeeds; that’s its core dice mechanic. On the surface, all dice just generate randomness, but the way that randomness is expressed shapes the whole experience. This first post defines what a core mechanic actually is, why simplicity and modifiability matter, and sets up a short series exploring how different dice systems create different vibes and outcomes.

Introduction

I’ve been asked to review a lot of systems lately, and I’ve noticed myself drawn immediately to an analysis of the core mechanic of the game in question. Long may this continue, but wouldn’t it be helpful, thought I, if there was some well thought out way for me to sort and identify techniques, using common language and a clearly developed pitch regarding what does what well?

Well, soon there will be. This is part one in a mini series that’s going to be a little self indulgent exploration of core dice mechanics.

What is a Core Dice Mechanic?

All RPGs, at least all the ones I’ve played or seen, involve a gameplay mechanism for introducing uncertainty over the outcome of player actions, and the uncertainty is the point. Without it, there’s no tension or surprise, and no sense that player choices might actually matter.

So to be clear, this uncertainty doesn’t just randomise outcomes for the sake of it, it injects suspense so nobody (especially not the GM!) can predict what’ll happen next.

Now often there’s one overriding procedure for this upon which all other sub mechanics are related to. A core mechanic therefore, is the single recurring way a game decides success or failure. Nearly every roll eventually points back to it.

All TTRPG’s needs a way to answer the question, “Does the action succeed?” But how that answer is generated, and how it feels is the heart of a well defined system.

Versatility, Not Complexity

Take for example, D&D 5e: Roll a d20, add your relevant modifiers and aim to meet or beat a DC set by the GM. This same mechanic is then recycled in combat in the same way: roll a d20 add a different modifier, and meet or beat the target’s AC.

In this way, you could argue that 5e’s mechanic is both simple and versatile. Which is important, because when you have lots of wildly different methods and processes to follow, then you’ve entered the territory of “complicated” and it’s cousin; “confusing”.

I’m a firm advocate that that’s something to be keenly avoided because any jock with an imagination can keep piling processes and mechanics onto a game system, but a talented designer knows it’s more about killing your darlings, and whittling away the chaff to unearth of the gem at the centre.

Modifiable, Not Messy

Good core mechanics should also be neatly modifiable to reflect tweaks that the GM might like to make to your odds of success. Let’s be absolutely clear here - fundamentally, that’s all you’re trying to accomplish – reducing the odds of success from 66% to 33%, or whatever you need to do.

So again, the core mechanic should lend itself to simple modifications: to this end, in 5e for example, we have advantage/disadvantage (roll two d20 and keep the best/worst result) and adjusting the DC according to what the GM deems fair. Other systems go their own way, but they all should have comparable functionality to this.

There is a trap there connected to modifying core mechanics, that is: don’t overwhelm the core mechanic with variable options. Options create analysis paralysis and stress. If you’re running a game, you’ve got enough to think about without repeatedly having to decide which lever to pull to achieve the same impact of affecting the odds of success for a given roll.

So to put it simply; you can tweak difficulty and/or tweak circumstance but anything more than that, and you’re pulling too many levers for one simple outcome.

Thesis: One RNG Is Much The Same As Another RNG - Right?

This brings me onto what I really want to explore in this mini series. Are all core dice mechanics doing the same thing? Are they interchangeable or do they lend themselves towards different subsystems? Do they vibe differently and affect the game’s tone?

I suspect not. But more than this, I expect it'll be interesting to deep dive into these questions.

In the meantime, I had a run down of my games shelf as well as all the games I’ve reviewed this year and created a list of all the different expressions of key elements of the dice loop for core mechanics:

Dice used

d20

d100

d6

Step dice

Objective

Roll over

Roll under

Count number of successes

Degrees of success/failure determined by

Not applicable

Critical success/fail

Highest/lowest natural result

Rolling a “double”

Rolling over 90th percentile of stat

Over/Under TN/stat by absolute amount

Over/Under TN/stat by percentage

Number of successes rolled

Variables dictated by the GM

TN

Positive/negative modifiers to dice result

Step dice rolled

Dice pool size

Advantage/Disadvantage

Variables dictated by character stats

Positive/negative modifiers to dice result

TN

Dice pool size

Step dice rolled

Phew, there’s a lot there to consider. Definitely one for another day me thinks.

Conclusion

This was just part one, an appetizer so to speak. Next time, I’ll start breaking these down. Modifiers, targets, roll-under, roll-over and see how those tiny shifts in probability shape entirely different kinds of games.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running!

Catch you laters, alligators.

The Seven Elements of West Marches Play

The West Marches is a style of TTRPG gameplay designed by Ben Robbins, and written up in 2007 on his Ars Ludi blog. The idea was that Robbins was burnt out as a GM, and bored of that mid campaign settlement where the players have lost some degree of enthusiasm for the ‘plot’ and are pretty much just going through the motions of turning up and rolling dice, then going home again. Rinsing and repeating each week.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap

TL;DR:

West Marches campaigns hand more responsibility to the players: no scripted plot, no encounter balance, and strict timekeeping. The GM builds a world of rumours, dangers, and discoveries, while the players organise sessions, keep records, and decide where to explore.

Introduction

Ahoy there. Apologies if I’m a little late with this post, and if the writing’s a little more concise than normal. I’ve got the dreaded COVID lurgy and thinking straight is a bit of a mission right now :D

Today’s post is inspired by two things. Firstly, Critical Role season 4, and the perhaps clumsy(?) mention that it will be in West Marches style, and secondly, that maybe the West Marches style will suit my upcoming Pirate Borg campaign. We’ll see, but these are my thoughts so far.

Why Do A West March Style Game?

The West Marches is a style of TTRPG gameplay designed by Ben Robbins, and written up in 2007 on his Ars Ludi blog. The idea was that Robbins was burnt out as a GM, and bored of that mid campaign settlement where the players have lost some degree of enthusiasm for the ‘plot’ and are pretty much just going through the motions of turning up and rolling dice, then going home again. Rinsing and repeating each week.

Robbins wanted more, so based on his interpretation of the original 1970s playstyle, he coined/rediscovered/invented/reimagined a new/old style of play; the West Marches. The goals were threefold:

More player engagement, players who actually cared about the game world and wanted to discover it.

Less GM burnout from things like manufacturing and forcing complicated arching plots, or weaving in player backstories all while having to constantly juggle the pressure of not accidentally killing the players and cutting their stories short.

Fairer distribution of meta game responsibilities so that things like arranging dates and times of play, and sharing things like after session reports and maps was a responsibility for the players rather than the GM.

Robbins had more players than table space, and he wanted to find a way to allow them all to share the same instance of the game world.

The Key Principles of West Marches

1) No Predefined Macro Level Plot

West Marches games are unapologetically sandbox in style. That means that the GM has absolutely zero responsibility for attempting to craft a narrative story with character arcs.

Instead, the story of the game is told in retrospect and is crafted by the player’s choices, and the judgements of the dice.

None of this is to say that that the GM’s world shouldn’t have a history though - craft a world to your heart’s content - just don’t craft a series of future events designed to happen at designated points in the upcoming campaign. For example, you may have a big bad evil guy, but you must not have plans to bring him out on the final session. If and when he arrives in the game will be driven by the players actions.

2) Exploration and Discovery Focus

There is a huge emphasis upon the exploration pillar - that is; the means by which exploration is handled, and the player’s desire to discover the secrets of the world and plunder its loot. How you handle the mechanics of travel is up to you, but the key is moving the players into the wilderness.

In order to motivate players to the leave their home base, Robbins suggested making it a safe haven for rest and shopping, but not a place where adventure can be had or knowledge can be attained. In fact, the world is often built so that the further you travel from base, the greater the dangers and the greater the reward.

Taking a slightly different route, I’m going to experiment with having all of the home base elements of the game happen away from the game table to be managed entirely between games, so that the actual sessions start and end with leaving and arriving back at home base.

3) No Encounter Balance

The GM should pay no heed towards trying to keep the player characters alive in the face of their poor choices. It is this perceived deadliness which drives the players to advance in the game and find ways to meet their own goals. When a band of player characters return back to base in failure, they return with a greater understanding of the challenges that lie ahead so that they might try again, better prepared next time.

Besides, I find that as with most things in life, all the juice is in the journey rather than the destination. That is, the striving toward success, not the actual succeeding.

To be blunt - this means, yes, player characters will die. Probably frequently. When they do, roll up a new one. This means that in turn, that adventuring groups will contain characters of different levels, and that’s OK too. When games are engineered this way, the focus of game play becomes less about your stats and abilities on a character sheet, and more about your abilities as a player to effectively and creatively solve problems. That’s a feature, not a bug.

4) Players Are Incentivised to Write Up Session Reports

Players should be encouraged to keep up all the between-game book keeping as much as possible, and make it publicly available on some kind of digital sharing and communication platform. Discord seems like a solid choice. This is meant to simulate the natural flow of stories and rumours that would happen when an adventuring party got back and hit the local tavern, and it’s a crucial shared resource for everyone. It plays a huge part in helping the players decide what they want to do next, especially when some players miss a couple of sessions and might not otherwise know what’s going on.

Be warned though, the GM should never be tempted to correct the player’s imperfect interpretation of the world, be that maps they have created and updated, or reflections upon a session’s activity. Nor should you correct your world to match their version - let the players discover for themselves where mistakes were made and correct them as the course of the adventure unfolds.

All that said, I think it’s very likely that players will need to be highly incentivised to do this, as most are used to being passive consumers of content - and now we’re effectively saying that we expect them to complete homework. I’ll experiment with using meta currency, or even XP as incentives until I find something that works.

5) Activity Driven by Rumours and Clues

As GM, you’re predesigning the world with care. Each location in the game’s world should be keyed and intentionally formed, and each should contain clues pointing to another location that ensures the players are never without tantalising options for future adventures.

Equally, I’ll also be using the between-session time to post rumours to the campaign discord which reflect what the players might have heard in the local tavern. There’s no pressure on the players to pursue these rumours and not all of them will even be true, but they will serve to stop the players from ever being short of options.

6) Player Responsibility To Arrange Sessions

This is a big one. Based off all the information players have received both in game, from rumours and from write ups, the players arrange between themselves where they want to go to next. If you’re operating with more than ones table’s worth of players then some will miss out on a particular adventure, and if they’re eager, they’ll set up a rival party to maybe head out to the same location to try to get the loot first.

Either way, when a group of players have come together to agree what they want to do next, and when and where they want to do it (they need to make sure the GM is also available and has enough notice to prepare) then they simply book the time in on the Discord server, or wherever you’re tracking your campaign, and provide details of the in-game date that the expedition is going to set off.

7) Strict Timekeeping Must be Kept

Firstly, before I get into it, your GM life will be made so much easier if you enforce an in-game rule that all adventuring parties must end their session at home base. If this involves having to come up with suitably punishing rules about ‘rolling to return home’ then so be it - it’s worth it for the headaches it saves. Let me explain why:

This is probably the biggest complication with running West Marches style games. As GM, you have to manage the passage of in-game time really carefully and accurately. If you do have multiple groups then the main headache will be in keeping track of branching timelines when a group departs, and then folding those timelines back into the main branch when the adventurers return back to base. All this has to be done in way that avoids creating any in-game ‘crossing of the streams‘.

For example; lets say you have two groups. If group A departs on the 1st day of your in-game calendar for location Z, and then they return on day 4, that represents a branch. The implication of this; is that later on in real time, group B cannot arrange a session where they depart on day 2 for location Z also. Why not? Because it would create a conflict - group A did not meet group B at location Z during the period of days 1-4, therefore group B cannot have gone there.

It would however be fine for group B to set off to location Y on day 2 and return on day 5. This doesn’t cause a conflict. They could also set off for location Z on day 5, but they’d be arriving at a place that’s already been visited.

At some point, your play groups should intermingle and form new groups. In these cases it is important to resolve any calendar differences between the different characters. Following our examples, for some PCs it is day 5, and for others it’s day 4. In these situations, we use downtime for the players on day 4 to fast travel them forwards to day 5. Alternatively, we fast travel everyone to whatever agreed day the next expedition happens on.

For me, this ‘downtime’ is the opportunity for players to shop, train, heal, carouse, careen their ships - whatever seems reasonable.

You’re gonna need a digital calendar to track this so that everyone knows what’s going on.

Additional Considerations

Consider Giving the Players A Basic Map

Not essential, but you might want to consider giving the players a starting map. Not a hex map, mind - nothing gamefied. Just a basic outline of the land, something that they can fill in as they go.

Multiple Groups or One Group

You can do this with only one table’s worth of players, that certainly simplifies the timekeeping, but it does mean that you’d be missing out on a key component of West Marches play - inter-player competition, and a sense of urgency to be the first to discover somewhere and get the loot.

That’s a big deal and one of this methods key draws.

Emergent Gameplay Vs Prep One Session at a Time

This isn’t an either/or situation. You should prep what you can for a given session once you’ve been informed of the players intent, but as with any style of TTRPG GMing, you should also have all the tools you need to hand to help you improvise emergent play when things take a turn for the unexpected.

Tools of the Trade

Just a quick list of some essential tools… Well, I think think they’re gonna be essential:

A private discord server, fully set up with different chat rooms for different purposes such as arranging sessions or sharing reports.

Maybe something like Obsidian Portal so that players can share their understanding of the world in a structured way.

Both an in-game calendar for planned expeditions, and a real world one for plotting game session on!

It’s all gone wrong!

There are a few pitfalls to watch out for I reckon, the key things to watch out for are:

Players forming cliques and never mixing with other players. You should make rules to force players to mix it up every once in a while.

Social barriers - such as players being bold enough to put themselves forward to actually arrange a session, rather than hoping someone else will do it, or players being too passive to bother with the after session write ups.

As GM, if you do need to break the rule about returning to base in the same session, you need to be really careful about how you handle it and the implications that this has on the timeline for everyone else.

Conclusion

My next move is gonna be to put this article in front of my play group and see if they’re interested. Maybe you can use it in the same way? If you’re interested in running West Marches style games, feel free to direct your players over this way to test the waters.

Also, I’ve never done West Marches before - if you have any advice or comments, please chuck it down below the line, I’ll be grateful of anything you can share!

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running!

Catch you laters, alligators.

D&D’s Best Intro Campaign? I ran Lost Mine of Phandelver For My Group

Lost Mine of Phandelver (LMoP) is the first D&D 5e starter set adventure. Released in 2014, LMoP is an event driven campaign for 3 - 5 players, taking characters from level 1 - 5.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap.

TL;DR: Lost Mine of Phandelver starts strong with tight early dungeons and a solid onboarding for new players, but quickly loses focus. The villain is forgettable, the pacing drifts, and structural choices teach new DMs bad habits like railroading and pulling punches. I rebuilt huge sections and turned it into a spaghetti western, giving the BBEG presence, adding time pressure, and replacing the green dragon with a recurring ancient red. The result was decent enough, but only because of heavy rewrites.

Run it as written and you’ll learn the hard way.

Introduction

Belch, Duncath, Twig, Diego, and Nasbo fire up the Forge of Spells.

From the shadows: slow clap. “Well done…” says the Black Spider, stepping into the dim light. “You have been my pawn from the start…”

Her skin tears away. Her back splits. The Black Spider crumples, replaced by an ancient red dragon — Dragos, the Destroyer of Worlds.

“Bow before me… or burn in this place!”

What is the Lost Mine of Phandelver?

Lost Mine of Phandelver (LMoP) is the first D&D 5e starter set adventure. Released in 2014, LMoP is an event driven campaign for 3 - 5 players, taking characters from level 1 - 5.

It took me several months of play to finish this, you could probably do it faster but we’re limited to 2-3 hours sessions twice a month.

That’s right folks, it’s another review from Jimbo about a product that’s been out for chuffin’ ages already! Wooo.

Spoiler Warning

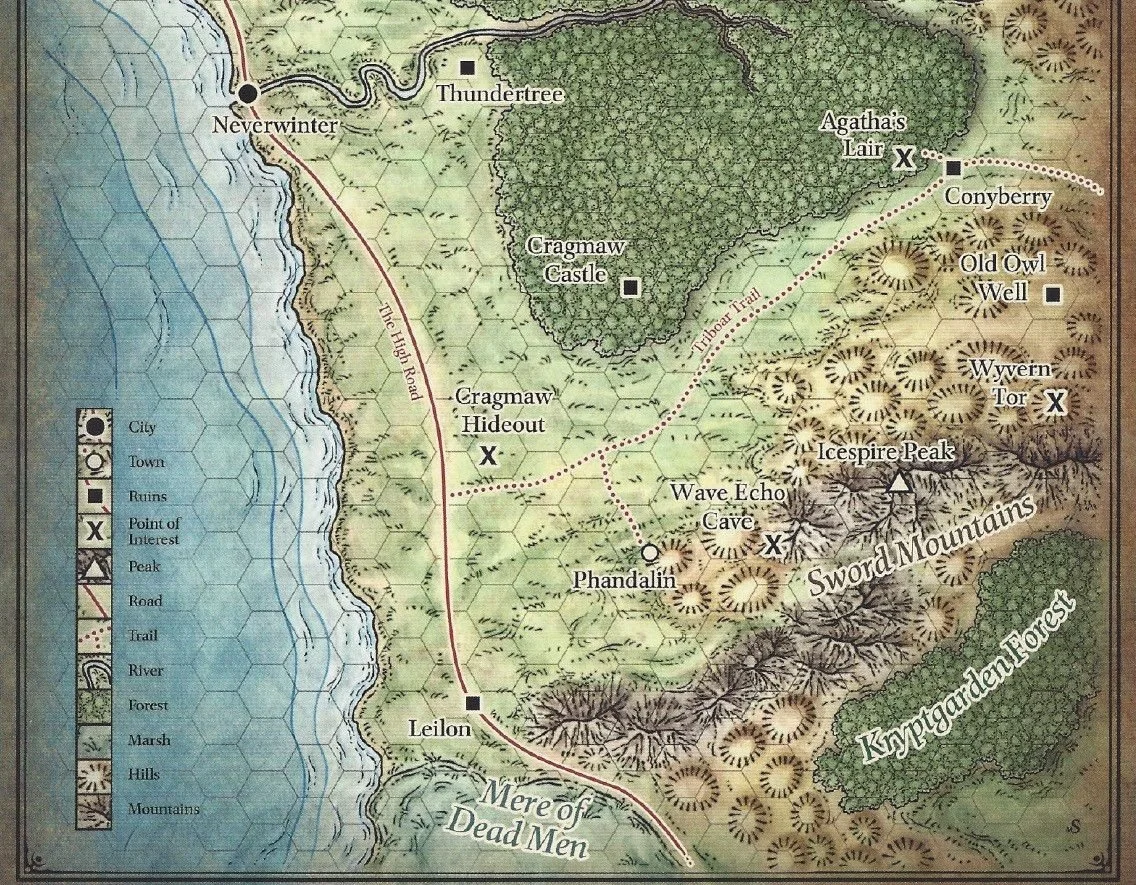

As written, the adventure is set on the Sword Coast, near Neverwinter, this dwarf dude named Gundren Rockseeker has found the legendary Wave Echo Cave (WEC), and the valuable Forge of Spells (FoS) within. He's recruited you to help him clear the place out and get it up and running.

The only problem is that en route to the frontier town of Phandalin, near WEC, Rockseeker is kidnapped by the Cragmaw Goblins, leaving you and your fellows to pick up the pieces.

The bulk of the adventure then follows the PCs as they attempt to find and rescue Rockseeker, discover the location of WEC for themselves, and thwart the various factions who're standing… sometimes in their way, and sometimes just off to the side.

This all ends with a fight against a BBEG you’d be forgiven for forgetting about called The Black Spider, who's been orchestrating all the local problems from the shadows like some moustache twirling villain out of a Saturday morning cartoon.

Ok, that's you all caught up.

So, What's it trying to do differently?

LMoP is a starter set, so it's trying to teach new DMs and players how the game works over the course of a strictly Event Driven Campaign (EDC). Emphasis on strictly, because all modules sit somewhere on a scale between sandbox and railroad. Well, this adventure sits at 90% railroad and IMO that’s too much for something that’s meant to set expectations.

The big problem here is that the EDC structure is a rigid sequence of set pieces where the players are nudged from one scene to the next. In my opinion, that’s a rubbish exposure to how an adventure should look for a new DM, and it’s a big reason you see so many online complaints about railroading from players regarding their lack of agency, and from burnt out DMs begging for help over their stress trying to force the flow of the game towards the predefined solution.

What does it do well?

Cragmaw Hideout in act 1 is a neat and concise little dungeon that does a good job teaching players about stealth, traps, competing factions, multiple paths and solutions. Aside from being too verbose, (which I’ll get to later) the dungeon presents a nice little challenge to the players, and is easy enough to run for the DM.

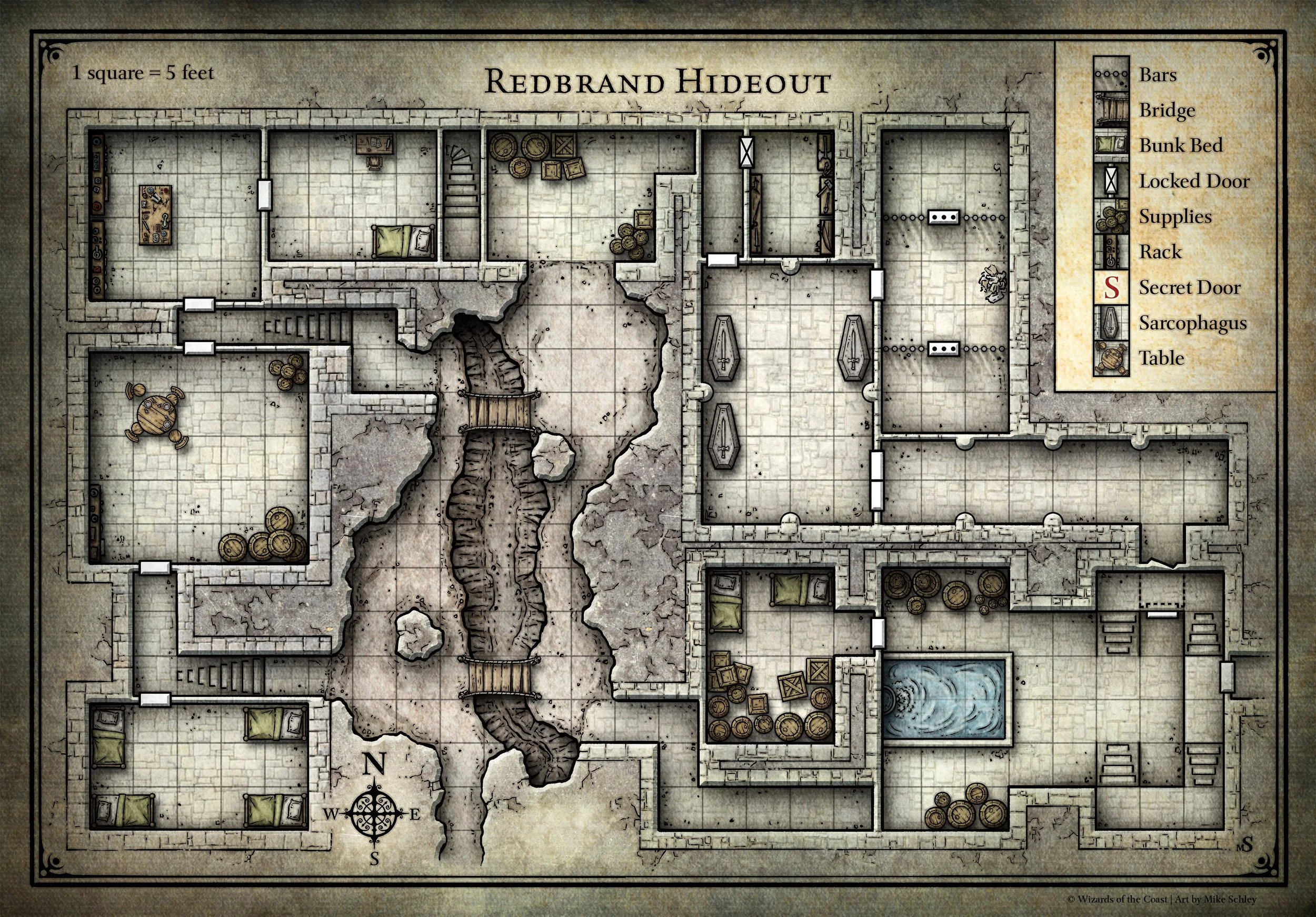

Redbrand Hideout too, is a little bigger but still very well designed and reinforces those lessons about multiple routes, traps, and adds rewards for extra exploration. It also includes a cool encounter with a Nothic which can lead to fun shenanigans - like sucking the skin off a willing dragonborn’s finger!

Finally I can confirm that this adventure contains both dungeons and a dragon, which at the very least earns it points for correct advertising.

Unfortunately that's about as much as I can honestly say that I thought was legitimately good. Everything else is 'meh' at best.

Yikes, I've got some beef. What didn't I like?

Deep breath.

Teaching the Wrong Lessons

Ok, so, as it's meant to be played the first encounter is a forced combat, seemingly 'balanced', and yet it's so deadly that any DM playing the ambushing goblins with any degree of tactical nouce should cause a TPK within a few turns. This is a terrible lesson - forced combats are bad enough, but making brand new DMs fight with one hand tied behind their back to give the fledgling players half a chance sets a bad precedent about expecting fudged rolls for both parties.

The text should acknowledge the deadliness here, and then give very specific guidance on what to do as DM if the player’s do not win.

Much later, Cragmaw Castle offers a false dichotomy. You see, players can go in the front door but that's obviously trapped, but if they do then it leads to several routes through the dungeon until the end and a potentially satisfying experience.. However, because of the aforementioned trap, the players do a quick bit of recon, and discover that they can just walk around the outside the castle and go in through the prominently placed side door with a simple pick lock check. After that they can chance upon skipping the entire dungeon by turning right on a whim and walking straight to the boss room with Gundren.

The game is trying to teach players that there are multiple paths and choices, but if one of those choices is obviously the right answer, then that's no choice at all - all we’re left with is an anti-climax.

Terrible Layout

Man alive, I hate long form text! If you want to run from the book (because, you know, that's why you bought a book in the first place) without having to spend hours rewriting and summarising it, then the DM is required to parse long form prose over several pages then flip back to a map for reference. This is no way to design an adventure, and it makes running scenes slow and easy to mess up.

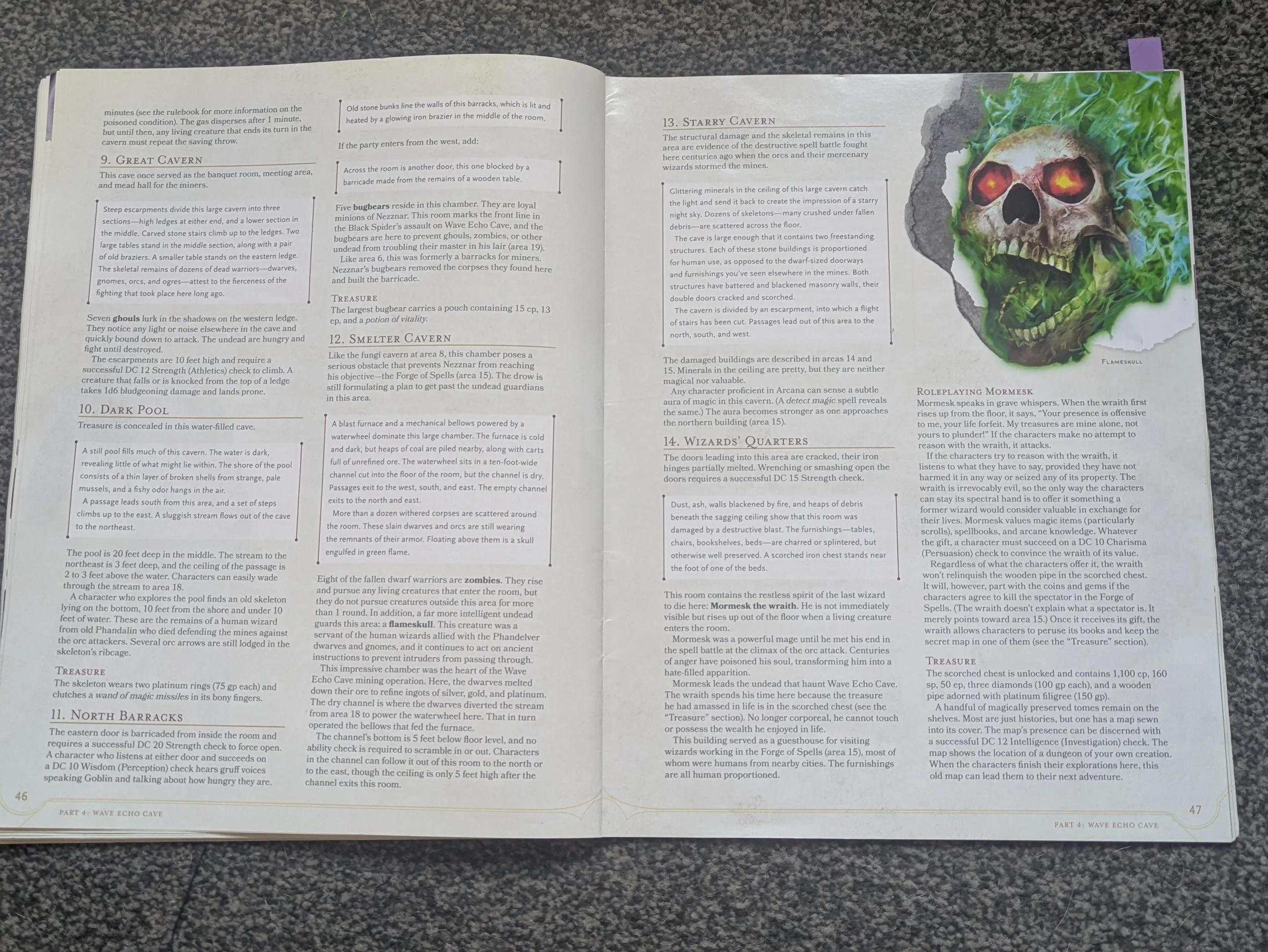

Below is just 2 pages from the 9 page WEC dungeon. Can you imagine trying to read that at the table, under pressure, and then articulate it back to your players? And those read aloud text boxes - my player’s would be asleep!

Half-baked “Story”

Gundren, the whole game is about rescuing Gundren, but other than a single boring real-aloud text box which mentions him at the start of the game - the players never meet him or have any genuinely gripping reason to care that he’s missing other than an underwhelming amount of GP offered as a reward.

In truth, the game comes with pre-gen characters that we didn’t use, and one or two of them have some tertiary connections to Gundren and Phandalin, but you don’t meet his brothers until the end so they’re not pressing you forwards, and the relationship Gundren has with Sildar is only mercantile, so why should he bust a nut begging for your help?

Then there’s the Black Spider. A BBEG that players just don't care about. As written, you never meet the Black Spider until the end, and you barely learn anything about them, their motives, or even that they're particularly evil or just misunderstood. That's a real kicker when you consider that this is so story driven - what's the point of a baddie if the players don't have an opinion about them?

It feels like ancient wisdom to say that a dragon that most players will never meet is no dragon at all. If a dragon falls over in the woods but no PC is there to hear it - does it still make a noise? Well, said dragon lives in Thundertree, which is so far removed from the main quest that I can't see many players naturally finding it without heavy DM fiat. What a waste of the game's only dragon!

Important DM Skills Completely Ignored

The game doesn't give you any tools to address pacing. Gundren has been kidnapped, but time might as well be standing still for days on end whilst you side quest. This should be used to teach DMs about driving urgency and hammering the game forwards with a simple GM facing timeline of steadily worsening events that happen if the PCs fail to act.

Speaking of act - after you finish up with the Redbrands, act 3 suddenly opens up into a sandbox which sends jarring messages about the game becoming a hex crawl. There’s only the most cursory guidance given to teaching DMs this new skill, and when the players have just experienced two acts teaching them that the game is a railroad about a time sensitive rescue mission, the sudden lack of direction brings the game screeching to a whiplash inducing halt.

Then, in act 4, WEC is such a large and boring dungeon that even the designers feel obliged to acknowledge as much. To combat this, rather than equipping the DMs with detailed knowledge about how to run a procedural dungeon crawl, the game settles for a quick paragraph about rolling a d20 on a random monster table according to GM fiat. This is not sufficient, not even close.

How did I run it?

I'm an experienced GM so after giving the game a cursery read through and seeing a tonne of things both objectively and subjectively bad, I had lots of work cut out for me to make a bunch of changes.

Some of those changes were quite experimental and not all of them worked as I'd hoped. We lives and learns, don’t we precious?

Setting

To start with - old forgotten mines, gangs, a frontier town... come on - this is a western, and yet, the game seems to forget this. Barely anything else nods towards this as the game defaults again and again to generic European fantasy land. Bugger that. So I reskinned it into a spaghetti western, including house-ruling in sixshooters. Much better.

Then, given my aforementioned loathing of long form prose at the table, I went through every dungeon and rewrote every room out for brevity and utility. Check out this post if you want to learn how to do this.

Goblin Arrows

This was really experimental, I ran act 1 as a lvl 0 gauntlet - each player had a cast of 4 characters each and whoever survived until after Cragmaw Hideout got to level up to 1, gain a class and became their primary character. This worked pretty well, but if you try it yourself make sure your players fully understand what's going to happen, as most of their characters will die by design and the players are expected to embrace this. It worked for me, just about - but you do you.

Phandalin

The cast of Phandalin got pruned down to just a few memorable NPCs. One of Gundren’s brothers was dead from the start, murdered by the Redbrands to push that conflict to the front. Sister Garaele became possessed by Agatha the Banshee, forcing the party to solve that before they could get her help.

I got rid of Thundertree as well, it's too far away from the adventure site and has absolutely nothing to do with anything. I also swapped out the young green dragon who lives there with an ancient red dragon; Dragos, Destroyer of Worlds, and I had him turn up every now and then as this ever present threat to extort treasure from the players. Man, they hated that dude!

The Black Spider was given presence. Introduced early under the guise of a serving girl at the Sleeping Giant Inn, I had her and the party competing to secure a lockbox (Thanks Matty P) containing a vital key to the Forge. She even kidnapped a beloved NPC, turning her from an abstract villain into someone the players actively hated.

The Spider’s Web

In Act 3, I tried expanding Old Owl Well into a full “funhouse” dungeon, and even though it was cool, it heavily distracted from Gundren’s rescue and confused the group about what mattered. The lesson there was clear: trying to add sandbox elements into a strict railroad just muddies both.

By the end of the Old Owl Well thread my players had pretty much forgotten all about Gundren, so I very quickly abandoned the idea of the exploratory sandbox, and swiftly provided more clues to guide the players towards his rescue where I made liberal use of progress clocks to make sure my players knew what was at stake. That alone is responsible for rescuing the Cragmaw Castle session from being a massive anticlimax due to it's bad dungeon design. If you want to learn about how and why to use progress clocks, check this post.

Wave Echo Cave

Wave Echo Cave was rebuilt into something tighter and easier to run. The maze became a tense skill challenge instead of a drawn-out slog.

At the climax, I revealed that the Black Spider was actually Dragos all along, which was a nice twist. One of my players even sided with the ancient red dragon whilst the others chose to fight, which gave me the opportunity to finish a campaign my favourite way - with a massive PvP monster bash.

You see, I placed 5 pilotable stone golems in the FoS chamber, and when battle commenced, the players used these in their combat against Dragos (who was controlled by the player who sided with him) - it was awesome and played out like the finale of an episode of Power Rangers, whilst I got to sit back and watch this really tightly fought match between titans.

What do other commentators say?

Matty P over on YouTube really likes LMoP, and I took a lot of his tips to heart about improving the story and trimming some of the fat, over the course of his full playlist . Definitely worth watching if you're planning on running it.

Conclusion

In the end, I have mixed feelings about LMoP, but I'm unfortunately leaning towards it being a bit pants. I really enjoyed acts 1 and 2, but the adventure rapidly drifts away from focus in act 3. additionally, for a game all about a prewritten story, said story requires a major rewrite to make it satisfactory.

Also, as a starter set to introduce new players and DMs to D&D, I think it probably does more harm than good if I'm being honest. I'd like to try to excuse it's flaws by saying it's really old, but frankly, there are starter adventures for earlier editions that have existed for much longer and nail it - Keep on the Borderlands anyone?

I guess I enjoyed myself running it, but only because I enjoying playing games with my friends, and maybe that's enough for you too? That said - I would have enjoyed myself even more running something better.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running!

Catch you laters, alligators.

6 Games that nail What Rules-Lite TTRPGs Should Be

A good rules-lite system doesn’t overwhelm you with procedures and crunch for every situation. Instead, the key procedures are covered and it gives you a clear, concise core mechanic. Then it trusts you to apply it flexibly.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated Tabletop Gaming Chap

TL;DR - Rules-lite isn’t the same as rules-incomplete or rules-inconsistent. Don't conflate them.

This post contains affiliate links.

Introduction

I want more people to play Rules-Lite games, but this crusade of mine is hindered by a misconception of what a rules-lite game actually is.

A lot of people hear "rules-lite" and think "lazy" or "half-finished." But that’s missing the point entirely. A great rules-lite RPG isn’t undercooked, it’s efficient, elegant, and focused. Let’s unpack what makes a minimalist system actually good, and why "less" doesn’t mean "worse."

What Is Rules-Lite

A good rules-lite system doesn’t overwhelm you with procedures and crunch for every situation. Instead, the key procedures are covered and it gives you a clear, concise core mechanic. Then it trusts you to apply it flexibly.

It’s just like that old saying:

Give a GM a fish, and they can run a session. Teach a GM to fish, and they can run a campaign.

Or something like that. I don’t know, it's close enough.

What isn’t Rules-Lite?

Let’s be crystal clear, rules-lite is very different from rules that are simply incomplete or inconsistent.

Inconsistent rules happen when a mechanic is explained more than once but the explanations don’t match. This usually signals a rushed edit. One version may or may not have replaced the other, but both made it to print. That’s not planned ambiguity, rather it comes over as just poor proofreading.

Designers: please, if someone flags this, don't try to convince us that you’re providing options. No one's falling for it, just own it and issue a FAQ or errata.

Incomplete rules are when a mechanic is introduced but not fully defined. For example, a game might explain how to hit an enemy in great detail… but never actually explain how damage works. You can’t convince me that this is minimalist design, it's just frustratingly half baked rules - because now we know that there is a specific way that this should be done, but we’ve no idea what it is.

RAI Matters

It all comes down to understanding the Rules as Intended (RAI). If the designer has said enough to give the GM an understanding of the game’s core rules language, then the GM should be confident that they can make a ruling that falls in line with RAI. If not, flesh it out some more.

Gameplay examples are great for this, as are developer commentaries in the sidebar. Designers take note!

Experience matters

I'm a big fan of the rules-lite philosophy, but if you've never run a TTRPG before, there is a danger that you might not have developed that muscle yet which allows you to make rulings up on the spot that feel consistent with the game system. Just bear that in mind before you pick your first game.

That’s not to say that a rules'-lite game shouldn’t be your first, but rather that I just want to make sure that your expectations are managed. It may start difficult, but it will get easier as you go on.

Recommendations

If you’re interested in picking up a good rules-lite game, then I’ve got a short curated list for you of some of my personal favourites. Full disclosure though my dudes, some of these are affiliate links, and if you chose to pick one up using the links provided, then I’ll get a small kickback at no extra cost to you.

Mausritter

Mausritter is a charming, rules-lite fantasy RPG where players take on the roles of brave little mice in a big, dangerous world. Built on Into The Odd, an OSR style framework, it uses simple d20 roll under mechanics and item slots for inventory, making it quick to learn and run. Its elegance lies in its ability to deliver rich, old-school adventure vibes with modern usability and 1990’s Disney cartoon flair.

I played in a duette game of this with my wife at the kitchen table, and she really enjoyed the vibes. With tweaks to the lethality I can see this being really popular with young families too.

Index Card RPG

ICRPG strips tabletop roleplaying down to its essentials with fast, flexible rules that encourage creative problem-solving and dynamic pacing. Everything runs off a single target number per room or scene, making it intuitive and highly adaptable. Its modular design and DIY ethos make it perfect for GMs who like hacking and building custom worlds on the fly.

EZD6

Created by DM Scotty, EZD6 lives up to its name with a system that’s incredibly easy to pick up and play. Most rolls come down to a single d6 against a target number, streamlining gameplay while leaving plenty of room for dramatic moments. It’s especially good for narrative-driven groups who don’t wanted to be limited by predefined abilities on their character sheets, and instead want to freedom to narrate their abilities as they see fit.

One of my players who’d never GM’d before in her life ran a couple of us through a homebrew adventure using this system and it was an absolute blast.

Pirate Borg

Pirate Borg is a brutal, rules-lite game of swashbuckling horror on the high seas. Inspired by Mörk Borg, it mixes fast, deadly mechanics with punk rock layout and evocative setting material. It’s ideal for players who like their pirate adventures with a side of doom, decay, and dark magic, and who don’t mind their characters dying spectacularly.

The squint-and-it’s-historical side of this game has literally made me buy pirate history books and start listening to pirate podcasts. I love all that stuff now, and it takes me back to my childhood - playing Secret of Monkey Island on my big brother’s Amiga. Good times.

GOZR

GOZR is a wild, gonzo sci-fantasy RPG that feels like it escaped from the back of an '80s metal album cover. It runs on a straightforward d20 roll-over system and embraces weirdness at every turn, from its mutant characters to its DIY zine-style aesthetic. It's brilliant for groups who want something fresh, funky, and full of chaotic creativity without a ton of prep.

I also wrote an opinion piece for this game a few months ago which included a free system cheat sheet that I’d worked on with the help of the games designer to get players started sooner. Can’t recommend it enough!

Spellz!

Indie developer, Jake Holmes recently reached out to me on Bluesky with an interesting little one page rules-lite game he was working on called SPELLZ! The game is still in it’s beta testing phase and he’s taking feedback on it it, but for the price of totally free, and for the sake of reading less than a single page - it’s definitely worth a look in if you want to see just how lite the rules can go!

It’s a fast TTRPG where magic is improvised in real time using letter tiles. Players draw tiles and try to form words on the fly — the word they create becomes the spell, and its effect is narrated accordingly. Stronger or stranger words often have bigger effects, and failed spell attempts can backfire spectacularly, with the GM repurposing your discarded letters.

I’ve not played it, but I have given feedback on the rules which was promptly actioned. It looks quick, and perfect for creative groups who enjoy thinking on their feet, might even be a way to introduce TTRPGs to your mum, dad, and nan who’s idea of a tabletop game otherwise begins with crosswords and ends with Scrabble!

Heya, just a thought, if you want me to take a look at your game and feature it on the site, like SPELLZ! Then drop me a message, lets have a chat!

Conclusion

The key message here is that if you've been frustrated by rules-incomplete or rules-inconsistent in the past, please don't be put off a rules-lite system because you're assuming it's the same thing. It ain't. If you get overwhelmed by books the size of a university textbook and you want to start small, rules-lite could be for you.

And so endeth the sermon.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter!

This post contains affiliate links.