What’s The Story, Muthur?

To the point, tabletop gaming

Popular Posts

How To Run A Dungeon - Fixing The Lost Mine of Phandelver

Here’s the problem, if you grew up in the 90’s or later, and have only ever played 5e - it’s likely that your only detailed point of reference for what a dungeon experience is like comes from video games - maybe something like Zelda (Ocarina of Time - best game ever made. Fight me!) The issue here is that they teach the player that a dungeon is this linear place, to be solved in a set way, with battles in predefined places.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap, who’s having to write this on his wife’s laptop because his broke :(

TL;DR:

Lost Mine of Phandelver gives you dungeons but no guidance on how to run them well. Good dungeon play needs urgency, resource pressure, meaningful time tracking, and dynamic encounters. This post breaks down classic and modern dungeon crawl procedures; from Justin Alexander’s traditional dungeon turns, to The Angry GM’s Tension Pool, Goblin Punch’s Underclock, and Dungeon Masterpiece’s encounter tables — and then shows how to use them to make Phandelver’s dungeons tense, reactive, and actually fun to run.

Introduction

Are you trying to run Lost Mine of Phandelver? I ran it recently. Have you noticed how (despite being a ‘starter set’) it does absolutely nothing to teach you how to run a dungeon? Bummer right?! Literally - there’s arguably five dungeons in this module, and it doesn’t show you how to run them at all. In fact, the closest it comes is the final dungeon where it even acknowledges how boring it’s going to be, and weakly suggests rolling for random encounters on a d20 table as and when you feel it’s appropriate.

Do better, Lizards-Ate-My-Toast.

You see, if you don’t know what you’re doing with dungeons, they can very easily turn into this very boring, very samey experience, with your players meticulously checking every tile for traps as they move from room to room, occasionally interrupting monsters that have apparently been sat there for an eternity - waiting to meet the PCs! Meanwhile the PCs have been long resting every couple of encounters to make sure they’re at maximum power all the time. And my God, I’m bored just thinking about it!

The chief cause of this dry experience is that there's no urgency or risk management. So how do you get that, I hear you ask? Damned fine question if I may say so myself, pat yourself on the back. You my friend, should read on, because unless you’re particularly looking for a simple linear gauntlet of pre-defined encounters, you probably need a “Dungeon Crawl Procedure”.

What In The Name Of Sweet baby Jeebus Is A Dungeon Crawl?

Here’s the problem, if you grew up in the 90’s or later, and have only ever played 5e - it’s likely that your only detailed point of reference for what a dungeon experience is like comes from video games - maybe something like Zelda (Ocarina of Time - best game ever made. Fight me!) The issue here is that they teach the player that a dungeon is this linear place, to be solved in a set way, with battles in predefined places. It works in a videogame because of the spectacle and hand eye skill involved.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t translate well to TTRPGs I’m afraid and these games bear little resemblance to what a D&D dungeon is supposed to be.

The fact that people try to emulate these video game experiences is why they fall flat at the table. It’s why your players probably don’t like dungeons, and it’s why you probably don’t like running them.

So, What’s missing?

To run a better dungeon, I advocate for the following components:

There should be no predefined method or route for ‘completing’ the dungeon. The player’s motivations and methods should be their own, and you should expect them to shift as they learn new things and as the situation inside the dungeon develops.

The dungeon should be punishing, and it should be a place that drains resources which cannot be easily replenished whilst the characters remain inside. This could be HP, or light, or spell slots, or rations, or more likely - some combination thereof.

The dungeon should be dynamic. It should move and breathe, and be both proactive and reactive in response the player character’s trespass. There should be opportunities within for all the major pillars of play - combat, social, and exploration.

Time should matter, it should be tracked carefully. Time affects your resources, and the position of dungeon inhabitants, and wasteful players should feel all these factors as keenly as a pin in their arm.

Which brings us nicely onto the “how” part of this post. Well my dudes, you have options. You see, it’s been a hot minute since the 1970’s and quite a few people have stepped up to the mark and developed processes for running dungeons. Here’s a handful of them:

Dungeon Crawl Processes

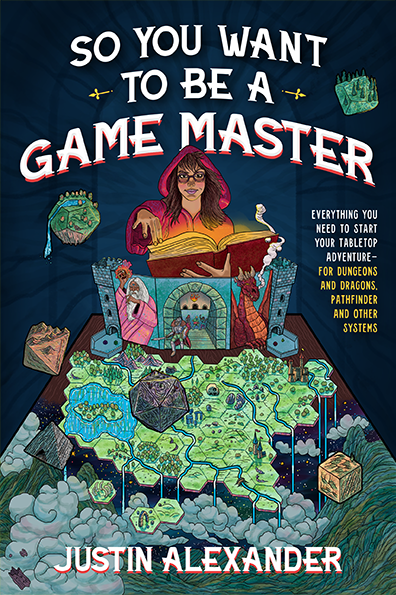

Justin Alexander - So You Want To Be A Game Master

In his book, Alexander explains a very traditional style. It’s a method that’s as old as the hobby itself, and it sets the fundamentals of most of the methods to follow - tracking time, resources, generating improvised encounters, and the concept of a Dungeon Crawl as a minigame within D&D as legitimate as combat.

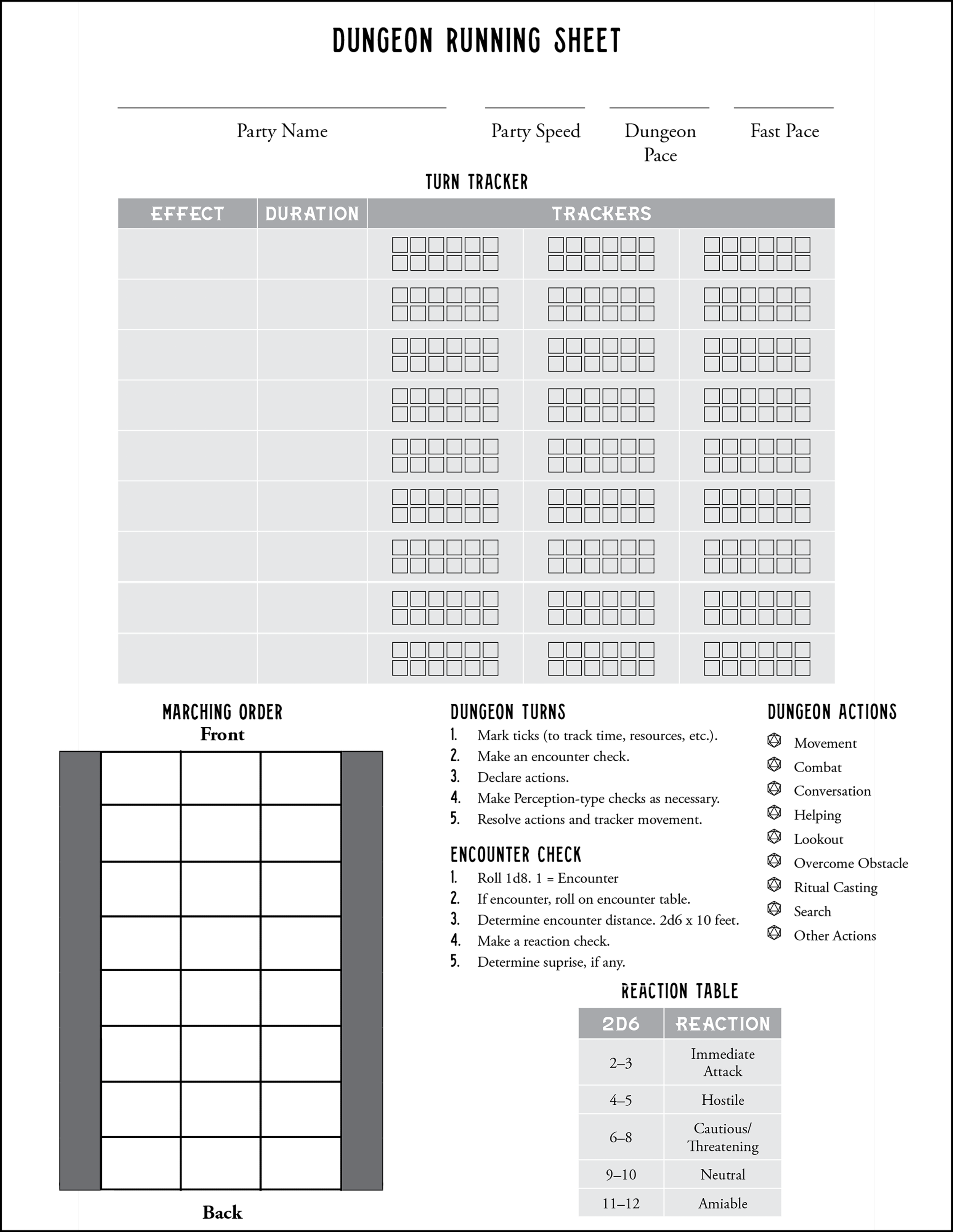

Marching Order

Getting players to declare a set marching order for the party up front solves a lot of hassles later on. As GM, now you know which characters are likely to trigger/spot traps, and which are likely to be picked off from the rear.

Dungeon Actions

After Marching Order, the next thing to define are the Dungeon Actions, these are not dissimilar in concept to the actions you can take in combat. Don’t read these as an absolute list, but rather as some common actions, which you can improvise upon as required.

This list includes, but is not limited to the following:

Move carefully (a snail’s pace. default movement speed to reflect the extreme caution of PCs moving through this pitch black, dangerous, scary environment).

Move fast (for when the PCs throw caution to the wind out of absolute necessity, or if they’re backtracking over a recently explored space).

Unlock a door.

Disarm a trap.

Investigate an area (getting more detail about some room feature than has been vaguely called out in the room overview).

Look for secret architecture (hidden doors, traps, pits).

Keeping watch (reducing/removing chance of being taken by surprise).

Casting a ritual spell.

Something else (talking to an NPC, loading your pockets with treasure, helping another PC, lighting a torch etc).

The idea here is that each player does one of these things per Dungeon Turn. Sometimes your players might want to do something so insignificant that you rule that they can have another action. This is fine. Trust your gut.

Dungeon Turn

This is an intentionally loosely defined amount of time - usually ten minutes (this is because ten plays nicely with many timed effects in D&D which are usually roundly divisible by this figure). Don’t sweat the precise granularity of it vs the actions taken in the Dungeon Turn, it requires not overthinking it in order to be effective.

Once the Dungeon Turn ends, the GM performs a bit of bookkeeping on their Dungeon Running Sheet. Justin Alexander features one on his website for you to print out and use:

The idea is that you record each ongoing item or spell effects duration per row, and then for each Dungeon Turn mark a tick in each row (all rows should read the same number of ticks in Alexander’s version, other designs may vary). When a given duration is met, that effect ends.

Whilst Alexander advocates doing this behind the scenes and making it feel less clunky and mechanically like a boardgame, other D&D scholars disagree. Dadi on Mystic Arts describes this process, but instead leans into the idea that the players should be aware of what’s going on behind the scenes to better inform their decisions, and thus debates.

You do you.

Regardless - there is one final step the GM takes as part of their bookkeeping.

Random Encounters

These are so important, and so many GMs are terrified of them in case they “ruin their story”. I say; it’s time to cowboy the chuff up, get comfortable with improv, and embrace the dice my friend! Seriously, stop worrying so much about game balance, and just trust your players to make the right choices to get out of whatever peril the dice serve up for them :)

Random encounters are valuable because they make your dungeon feel alive and dynamic. Rather than the players feeling safe that they can only encounter creatures as they travel to a new area, now, the creatures can come to them. Alexander recommends the following method:

Once you’ve done all your Dungeon Turn bookkeeping, roll a d8. A result of one means that an encounter will occur.

Roll on your pre-prepared Dungeon Encounter table to decide which encounter it will be.

Determine how far away the encounter is by rolling 2d6 x 10 feet.

Unless it’s obvious, make a 2d6 reaction check to determine the attitude of the creatures you’ve encountered. Not all encounters have to be fights.

Determine if one group is surprised by the other, usually Stealth vs Perception checks. Any players taking the ‘keep watch’ Dungeon Action infer a better probability of success here.

The Angry GM - The Tension Pool

One problem with the traditional method described by Alexander is that the only sense of increasing dread comes from resource drain. The odds of an actual encounter remain static, and this effects the psychology of the group if you’re trying to foster a sense of ever creeping doom!

Responding to this shortfall, the Angry GM has a nifty little replacement for traditional random encounter checks called the Tension Pool and it all starts with a glass bowl.

Each Dungeon turn, toss a d6 into the glass bowl (AKA the Tension Pool). This should be visible to all the players. Then:

Each time during a dungeon turn that a PC does something risky or noisy, you roll any dice in the Tension Pool. Results of six prompt a roll on your pre-prepared encounter table.

Each time the Tension Pool fills up with 6d6, roll all the dice in the Pool as above to check for encounters, and then reset the pool to zero.

This is pretty cool, two things are happening:

We’re tracking the passage of time, with a dice in the pool representing a dungeon turn.

The likelihood of a random encounter is visibly impacted by the passage of time and the actions of your players.

That said, not everyone agrees that this is enough, I reckon that with a small modification, you could also use this to abstractly track effects using different colour dice of different denominations. For example, if someone lights a torch, toss in a d8 (or whatever seems right - I’ve not play tested this). The d8 will never trigger an encounter check like a d6 does, but each time the pool is rolled, that d8 might come up with an eight, and if it does - the torch is snuffed out (and the d8 is removed).

This way that’s less stuff to track on a piece of paper, and we’ve also now baked in variance on item and spell effect durations - if that torch goes out, maybe it was a gust of wind? If a spell effect ends, maybe the caster tripped on a flagstone and lost concentration?

Goblin Punch - The Underclock

Arnold K over at Goblin Punch has an entirely different method for using random encounters to build tension. He calls it the Underclock and it works like this:

Grab a d20, a nice big one. Or use a piece of paper, or a paper dial, or whatever you have that can track to 20. This is the Underclock, keep it out in the open so the players can see it.

Starting from 20, each Dungeon Turn the GM rolls a d6 and subtracts the result from the Underclock value.

Results of six on the d6 explode (this means you roll an additional d6).

When the Underclock hits less than zero it triggers an encounter on your random encounter table. At zero exactly, the clock resets to three instead.

If the Underclock ever reads three, a foreshadowing event occurs and the PCs learn a clue about the nature of the impending encounter (naturally, you’ll have to roll the random encounter at that point for your own reference).

The nice thing here is the players are more informed (but not perfectly so) about when an encounter is due. You can represent this as them hearing noises, or ‘spidey sense’, or whatever works for you.

This forewarning means that the players have another interesting decision to make - do they press on, do they try to hide, or do they prepare an ambush instead?

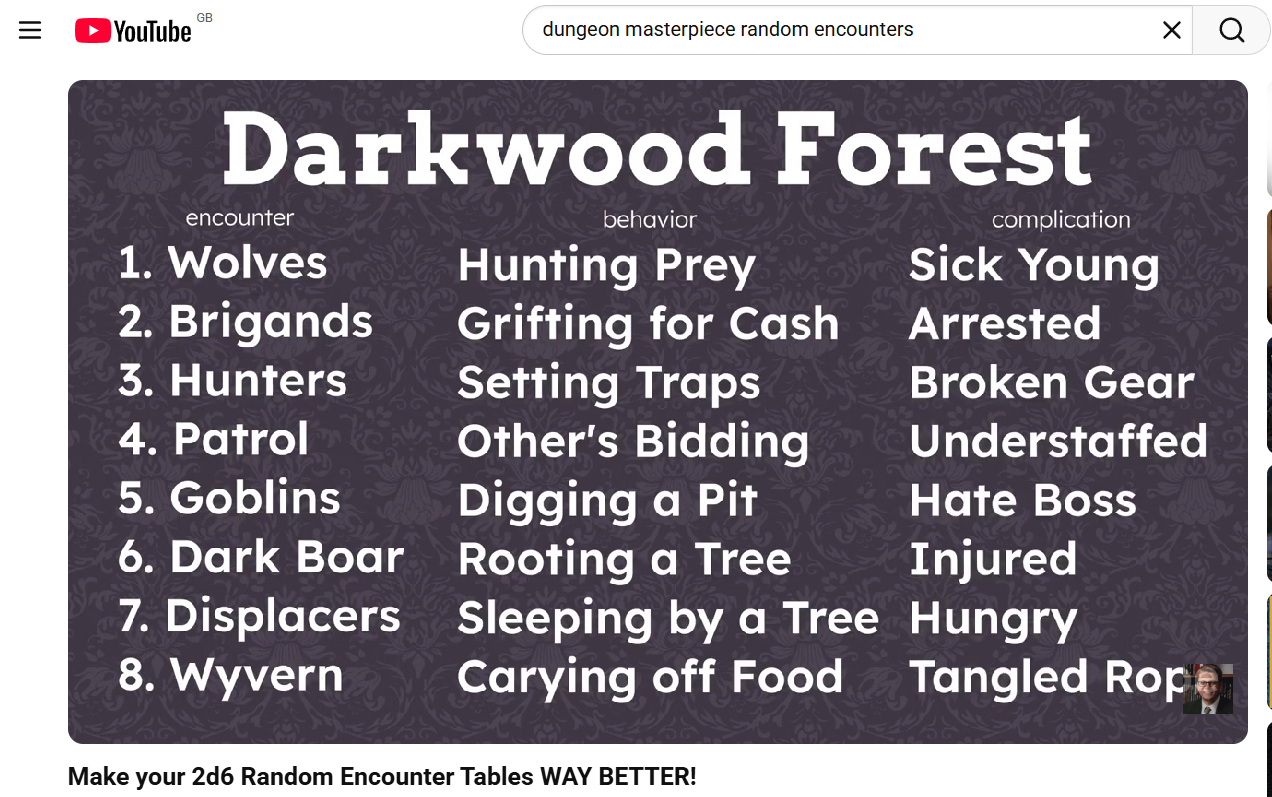

Dungeon Masterpiece - Random Encounter Tables

Baron de Ropp at Dungeon Masterpiece makes an excellent point regarding Random Encounter Tables.

Traditionally, they’re either single die table of possible encounters, or they’re a multi-dice table, which introduces a bell curve only the range of outcomes. Then on top of that you layer distance and reaction.

De Ropp highlights that this structure alone does not do anything to weave a larger narrative together, nor is it scalable, nor does it do much to help the GM to come up with a unique yarn to spin about the specific encounter.

To resolve this, he has a number of tricks:

If you have quests and rumours planned out - seed these into your random encounters. That pack of wolves you just defeated, maybe one of them had a golden arrow buried in its flank. Who made the arrow? Perhaps there’s someone in the woods that specialises in such trinkets?

If your table contains six entries, corresponding to a d6, why not add two more entries to it. Order the tables by difficulty, and then as your players advance in skill, add +1 or +2 to their dice result to weigh the results in the favour of more difficult encounters.

This one’s the real juice. De Ropp suggests adding two more columns to your random encounter table. Behaviour and Complication. You fill these in on a per row basis in a way that makes total sense for that given row. For example - Wolves. The behaviour might be “Hunting Prey” and their complication might be “Their pups are sick”. Here’s the clever bit - you roll three times on the random encounter table, generating a potentially different row per column. You might come up with “Goblins”, “Grifting for Cash”, “Their pups are sick”. This is your improv prompt for the scene, and by combining the elements from different rows, you’ll come up with some really unique encounters.

I’m a big fan of building Encounter Tables this way, and aside from the small amount of extra prep work they take - there’s not really much in the way of downside that I recognise.

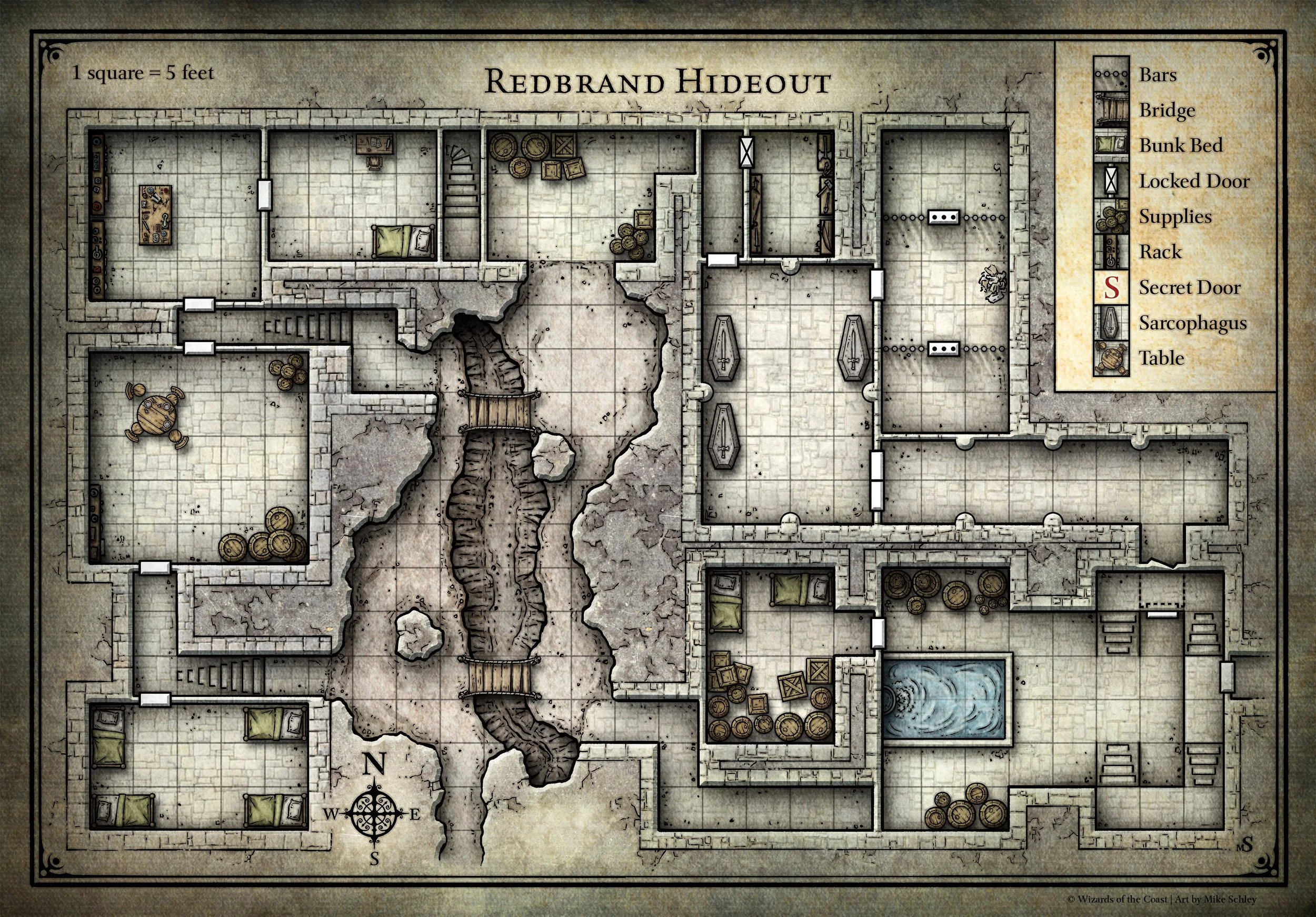

Conclusion

So there you go. Whether it’s the Goblin Caves, Redbrand Hideout, or Wave Echo Cave - you’ve now got a detailed set of options for running these dungeons in a way that’s time tested and true. Let me know below the line if you have any other tips for people looking to improve the way that they run dungeons.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running! If you’ve still got some time to kill, Perhaps I can persuade you to click through below to another one of my other posts?

Catch you laters, alligators.

D&D’s Best Intro Campaign? I ran Lost Mine of Phandelver For My Group

Lost Mine of Phandelver (LMoP) is the first D&D 5e starter set adventure. Released in 2014, LMoP is an event driven campaign for 3 - 5 players, taking characters from level 1 - 5.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap.

TL;DR: Lost Mine of Phandelver starts strong with tight early dungeons and a solid onboarding for new players, but quickly loses focus. The villain is forgettable, the pacing drifts, and structural choices teach new DMs bad habits like railroading and pulling punches. I rebuilt huge sections and turned it into a spaghetti western, giving the BBEG presence, adding time pressure, and replacing the green dragon with a recurring ancient red. The result was decent enough, but only because of heavy rewrites.

Run it as written and you’ll learn the hard way.

Introduction

Belch, Duncath, Twig, Diego, and Nasbo fire up the Forge of Spells.

From the shadows: slow clap. “Well done…” says the Black Spider, stepping into the dim light. “You have been my pawn from the start…”

Her skin tears away. Her back splits. The Black Spider crumples, replaced by an ancient red dragon — Dragos, the Destroyer of Worlds.

“Bow before me… or burn in this place!”

What is the Lost Mine of Phandelver?

Lost Mine of Phandelver (LMoP) is the first D&D 5e starter set adventure. Released in 2014, LMoP is an event driven campaign for 3 - 5 players, taking characters from level 1 - 5.

It took me several months of play to finish this, you could probably do it faster but we’re limited to 2-3 hours sessions twice a month.

That’s right folks, it’s another review from Jimbo about a product that’s been out for chuffin’ ages already! Wooo.

Spoiler Warning

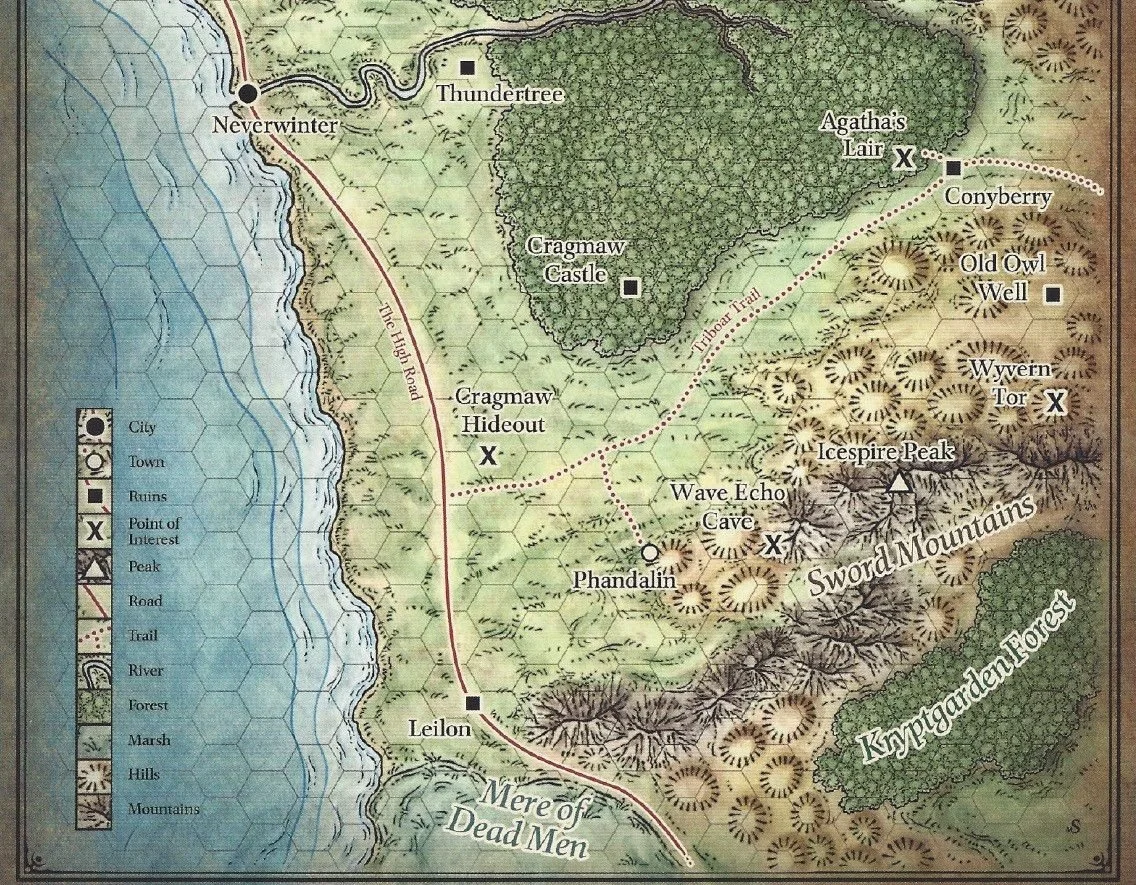

As written, the adventure is set on the Sword Coast, near Neverwinter, this dwarf dude named Gundren Rockseeker has found the legendary Wave Echo Cave (WEC), and the valuable Forge of Spells (FoS) within. He's recruited you to help him clear the place out and get it up and running.

The only problem is that en route to the frontier town of Phandalin, near WEC, Rockseeker is kidnapped by the Cragmaw Goblins, leaving you and your fellows to pick up the pieces.

The bulk of the adventure then follows the PCs as they attempt to find and rescue Rockseeker, discover the location of WEC for themselves, and thwart the various factions who're standing… sometimes in their way, and sometimes just off to the side.

This all ends with a fight against a BBEG you’d be forgiven for forgetting about called The Black Spider, who's been orchestrating all the local problems from the shadows like some moustache twirling villain out of a Saturday morning cartoon.

Ok, that's you all caught up.

So, What's it trying to do differently?

LMoP is a starter set, so it's trying to teach new DMs and players how the game works over the course of a strictly Event Driven Campaign (EDC). Emphasis on strictly, because all modules sit somewhere on a scale between sandbox and railroad. Well, this adventure sits at 90% railroad and IMO that’s too much for something that’s meant to set expectations.

The big problem here is that the EDC structure is a rigid sequence of set pieces where the players are nudged from one scene to the next. In my opinion, that’s a rubbish exposure to how an adventure should look for a new DM, and it’s a big reason you see so many online complaints about railroading from players regarding their lack of agency, and from burnt out DMs begging for help over their stress trying to force the flow of the game towards the predefined solution.

What does it do well?

Cragmaw Hideout in act 1 is a neat and concise little dungeon that does a good job teaching players about stealth, traps, competing factions, multiple paths and solutions. Aside from being too verbose, (which I’ll get to later) the dungeon presents a nice little challenge to the players, and is easy enough to run for the DM.

Redbrand Hideout too, is a little bigger but still very well designed and reinforces those lessons about multiple routes, traps, and adds rewards for extra exploration. It also includes a cool encounter with a Nothic which can lead to fun shenanigans - like sucking the skin off a willing dragonborn’s finger!

Finally I can confirm that this adventure contains both dungeons and a dragon, which at the very least earns it points for correct advertising.

Unfortunately that's about as much as I can honestly say that I thought was legitimately good. Everything else is 'meh' at best.

Yikes, I've got some beef. What didn't I like?

Deep breath.

Teaching the Wrong Lessons

Ok, so, as it's meant to be played the first encounter is a forced combat, seemingly 'balanced', and yet it's so deadly that any DM playing the ambushing goblins with any degree of tactical nouce should cause a TPK within a few turns. This is a terrible lesson - forced combats are bad enough, but making brand new DMs fight with one hand tied behind their back to give the fledgling players half a chance sets a bad precedent about expecting fudged rolls for both parties.

The text should acknowledge the deadliness here, and then give very specific guidance on what to do as DM if the player’s do not win.

Much later, Cragmaw Castle offers a false dichotomy. You see, players can go in the front door but that's obviously trapped, but if they do then it leads to several routes through the dungeon until the end and a potentially satisfying experience.. However, because of the aforementioned trap, the players do a quick bit of recon, and discover that they can just walk around the outside the castle and go in through the prominently placed side door with a simple pick lock check. After that they can chance upon skipping the entire dungeon by turning right on a whim and walking straight to the boss room with Gundren.

The game is trying to teach players that there are multiple paths and choices, but if one of those choices is obviously the right answer, then that's no choice at all - all we’re left with is an anti-climax.

Terrible Layout

Man alive, I hate long form text! If you want to run from the book (because, you know, that's why you bought a book in the first place) without having to spend hours rewriting and summarising it, then the DM is required to parse long form prose over several pages then flip back to a map for reference. This is no way to design an adventure, and it makes running scenes slow and easy to mess up.

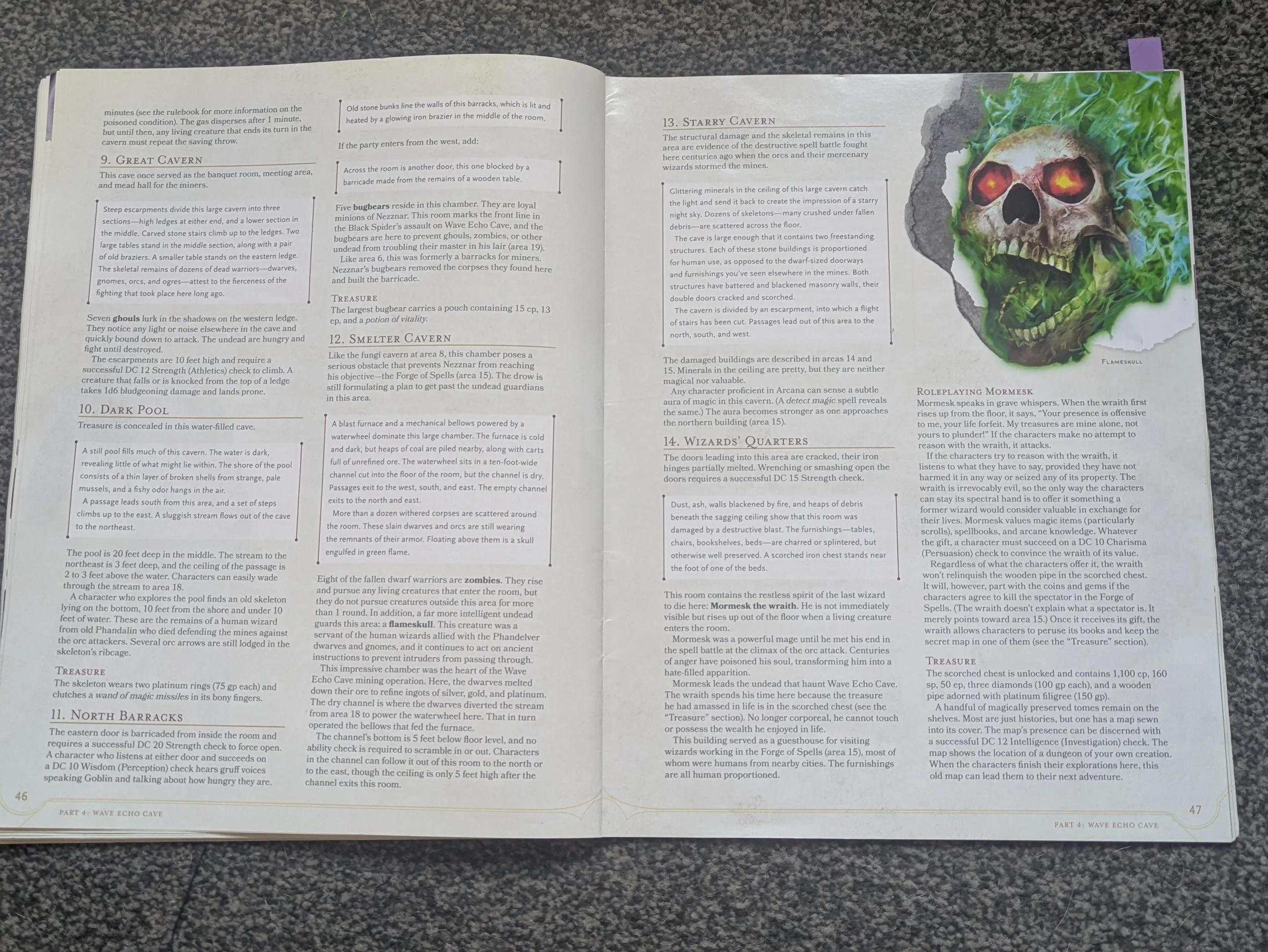

Below is just 2 pages from the 9 page WEC dungeon. Can you imagine trying to read that at the table, under pressure, and then articulate it back to your players? And those read aloud text boxes - my player’s would be asleep!

Half-baked “Story”

Gundren, the whole game is about rescuing Gundren, but other than a single boring real-aloud text box which mentions him at the start of the game - the players never meet him or have any genuinely gripping reason to care that he’s missing other than an underwhelming amount of GP offered as a reward.

In truth, the game comes with pre-gen characters that we didn’t use, and one or two of them have some tertiary connections to Gundren and Phandalin, but you don’t meet his brothers until the end so they’re not pressing you forwards, and the relationship Gundren has with Sildar is only mercantile, so why should he bust a nut begging for your help?

Then there’s the Black Spider. A BBEG that players just don't care about. As written, you never meet the Black Spider until the end, and you barely learn anything about them, their motives, or even that they're particularly evil or just misunderstood. That's a real kicker when you consider that this is so story driven - what's the point of a baddie if the players don't have an opinion about them?

It feels like ancient wisdom to say that a dragon that most players will never meet is no dragon at all. If a dragon falls over in the woods but no PC is there to hear it - does it still make a noise? Well, said dragon lives in Thundertree, which is so far removed from the main quest that I can't see many players naturally finding it without heavy DM fiat. What a waste of the game's only dragon!

Important DM Skills Completely Ignored

The game doesn't give you any tools to address pacing. Gundren has been kidnapped, but time might as well be standing still for days on end whilst you side quest. This should be used to teach DMs about driving urgency and hammering the game forwards with a simple GM facing timeline of steadily worsening events that happen if the PCs fail to act.

Speaking of act - after you finish up with the Redbrands, act 3 suddenly opens up into a sandbox which sends jarring messages about the game becoming a hex crawl. There’s only the most cursory guidance given to teaching DMs this new skill, and when the players have just experienced two acts teaching them that the game is a railroad about a time sensitive rescue mission, the sudden lack of direction brings the game screeching to a whiplash inducing halt.

Then, in act 4, WEC is such a large and boring dungeon that even the designers feel obliged to acknowledge as much. To combat this, rather than equipping the DMs with detailed knowledge about how to run a procedural dungeon crawl, the game settles for a quick paragraph about rolling a d20 on a random monster table according to GM fiat. This is not sufficient, not even close.

How did I run it?

I'm an experienced GM so after giving the game a cursery read through and seeing a tonne of things both objectively and subjectively bad, I had lots of work cut out for me to make a bunch of changes.

Some of those changes were quite experimental and not all of them worked as I'd hoped. We lives and learns, don’t we precious?

Setting

To start with - old forgotten mines, gangs, a frontier town... come on - this is a western, and yet, the game seems to forget this. Barely anything else nods towards this as the game defaults again and again to generic European fantasy land. Bugger that. So I reskinned it into a spaghetti western, including house-ruling in sixshooters. Much better.

Then, given my aforementioned loathing of long form prose at the table, I went through every dungeon and rewrote every room out for brevity and utility. Check out this post if you want to learn how to do this.

Goblin Arrows

This was really experimental, I ran act 1 as a lvl 0 gauntlet - each player had a cast of 4 characters each and whoever survived until after Cragmaw Hideout got to level up to 1, gain a class and became their primary character. This worked pretty well, but if you try it yourself make sure your players fully understand what's going to happen, as most of their characters will die by design and the players are expected to embrace this. It worked for me, just about - but you do you.

Phandalin

The cast of Phandalin got pruned down to just a few memorable NPCs. One of Gundren’s brothers was dead from the start, murdered by the Redbrands to push that conflict to the front. Sister Garaele became possessed by Agatha the Banshee, forcing the party to solve that before they could get her help.

I got rid of Thundertree as well, it's too far away from the adventure site and has absolutely nothing to do with anything. I also swapped out the young green dragon who lives there with an ancient red dragon; Dragos, Destroyer of Worlds, and I had him turn up every now and then as this ever present threat to extort treasure from the players. Man, they hated that dude!

The Black Spider was given presence. Introduced early under the guise of a serving girl at the Sleeping Giant Inn, I had her and the party competing to secure a lockbox (Thanks Matty P) containing a vital key to the Forge. She even kidnapped a beloved NPC, turning her from an abstract villain into someone the players actively hated.

The Spider’s Web

In Act 3, I tried expanding Old Owl Well into a full “funhouse” dungeon, and even though it was cool, it heavily distracted from Gundren’s rescue and confused the group about what mattered. The lesson there was clear: trying to add sandbox elements into a strict railroad just muddies both.

By the end of the Old Owl Well thread my players had pretty much forgotten all about Gundren, so I very quickly abandoned the idea of the exploratory sandbox, and swiftly provided more clues to guide the players towards his rescue where I made liberal use of progress clocks to make sure my players knew what was at stake. That alone is responsible for rescuing the Cragmaw Castle session from being a massive anticlimax due to it's bad dungeon design. If you want to learn about how and why to use progress clocks, check this post.

Wave Echo Cave

Wave Echo Cave was rebuilt into something tighter and easier to run. The maze became a tense skill challenge instead of a drawn-out slog.

At the climax, I revealed that the Black Spider was actually Dragos all along, which was a nice twist. One of my players even sided with the ancient red dragon whilst the others chose to fight, which gave me the opportunity to finish a campaign my favourite way - with a massive PvP monster bash.

You see, I placed 5 pilotable stone golems in the FoS chamber, and when battle commenced, the players used these in their combat against Dragos (who was controlled by the player who sided with him) - it was awesome and played out like the finale of an episode of Power Rangers, whilst I got to sit back and watch this really tightly fought match between titans.

What do other commentators say?

Matty P over on YouTube really likes LMoP, and I took a lot of his tips to heart about improving the story and trimming some of the fat, over the course of his full playlist . Definitely worth watching if you're planning on running it.

Conclusion

In the end, I have mixed feelings about LMoP, but I'm unfortunately leaning towards it being a bit pants. I really enjoyed acts 1 and 2, but the adventure rapidly drifts away from focus in act 3. additionally, for a game all about a prewritten story, said story requires a major rewrite to make it satisfactory.

Also, as a starter set to introduce new players and DMs to D&D, I think it probably does more harm than good if I'm being honest. I'd like to try to excuse it's flaws by saying it's really old, but frankly, there are starter adventures for earlier editions that have existed for much longer and nail it - Keep on the Borderlands anyone?

I guess I enjoyed myself running it, but only because I enjoying playing games with my friends, and maybe that's enough for you too? That said - I would have enjoyed myself even more running something better.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running!

Catch you laters, alligators.