What’s The Story, Muthur?

To the point, tabletop gaming

Popular Posts

Pirate Borg Factions - Blackbeard And The Scourge

Drawn by instinct deeper than memory, the corpse made its way toward Chesapeake Bay to reclaim what had been severed from it. When Blackbeard stood whole once more, something happened. Unlike the rest of the Scourge, he retained his will.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap

TL;DR:

An ancient Abyss awakens the drowned dead of the Caribbean. Blackbeard rises with his will intact, commands the Scourge, and sets out to break the English, control the ASH trade, and crown himself king of the Dark Caribbean.

Introduction

Ahoy. Did you catch my post the other week about the real history of Blackbeard? I said that I’d follow up with how I’ve built upon that real history to bake Blackbeard into the fantasy lore of Pirate Borg’s Dark Caribbean setting.

Well, this is gonna be just that, so buckle down your flintlocks and secure your cutlasses. Let’s goooo.

In The Beginning

I can’t jump straight to Blackbeard without first setting the stage. Much of my lore builds directly on the official History of the Dark Caribbean from the Pirate Borg Core Rules (p.25), with my campaign beginning in “Chapter 5,” where “Blackbeard, a sorcerer, returns from the grave with an army of the dead.”

But before those events and before the timeline in the book even begins, there are a few crucial pieces of history to establish.

Pre-History

Deep beneath the Caribbean Sea lies a cosmic scar. Gods only know how long it had been there or from whence it came. It’s a rift in reality that opens into an Abyssal existence beyond mortal comprehension. Madness made geography.

In ages long forgotten, proto-Mesoan peoples encountered this rift. In attempting to understand the madness and magic emanating from it, many souls lost their sanity. Those who studied and survived came to recognise the malign intent of the forces within.

Using rituals uncovered in their desperate search for meaning, they sealed the rift and constructed an aquatic city upon it — a living capstone over the wound. That city would become Atlantis, deep in the heart of what is today known as the Bermuda Triangle.

In time, the ancient Atlantean people fractured. The splitting branch, known as the Doradians, abandoned their watery city and journeyed to the mainland Yucatán, seeking distance from the source of their horrific dreams. There, their advanced culture endured in an altered form focused around a golden city.

Recently

Against the backdrop of the Greater Antilles War (The Caribbean theatre of the War of Spanish Succession 1701 - 1714), Cultists of the Wretched (disciples of the entity that dwells within the Abyss) dispatch an agent to the jungles of the Yucatán.

Among the ruins of the ancient Doradian culture, that agent became The Sunken One, and completed a ritual to relocate the Abyssal gateway - wrenching it free from the restraining powers of Atlantis and transferring the wound to the oceanic region South of Cuba.

The Abyss was no longer sealed. The resulting upheaval shattered the region, releasing unnatural magics in its wake. Port Royal was destroyed in the resulting earthquake.

Unintended Consequences

The Sunken One did not foresee what would follow: The Abyss is not a wound that can be exposed without consequence. When torn free from the ancient restraints of Atlantis, its corruption bled outward into the sea and to the sky alike, and the ocean began to remember its dead.

Sailors lost to storm and cannon, slaves thrown overboard, mutineers sunk in chains, entire crews swallowed by hurricane. The Caribbean now returns them all. These risen corpses became known as The Scourge, they aren’t clever or strategic, merely repeating the last violent patterns of their lives: boarding, burning, hunting, killing. They are driven by a rage which they cannot put words to.

But the Abyss does not act within boundaries. It did not take long for the corruption to reach the waters off Ocracoke Island. There, in the shallows where his body had been cast aside, one Edward Teach rose again.

Drawn by instinct deeper than memory, the corpse made its way toward Chesapeake Bay to reclaim what had been severed from it. When Blackbeard stood whole once more, something happened. Unlike the rest of the Scourge, he retained his will.

Whether this was design, accident, or selection, none can say. But the mindless dead began to gather to him. Ships crewed by the drowned altered course. The Queen Anne’s Revenge, more terrible than ever, returned. Silent decks turned toward his black flag.

The Scourge had found a king, Blackbeard found his armada, and the Caribbean found its Harbinger.

The Scourge As A Faction

I follow the Cairn 2nd ed school of thought for how to run sandbox factions. See this video by LowKeyTTRPG for more information about how that mechanically works - but in essence, you take a “faction turn” (roll some dice) between game sessions. Factions should have goals that the players can feel the affects of and their success in terms of their goals should be a product of the resources they have available to them vs the obstacles in their path.

If we look at Blackbeard’s real history it stands to reason that he’d be motivated by revenge, and a lust for power and reputation. With that in mind I’ve got three goals for the scourge under Blackbeard:

1) Break The English in the Caribbean

Humiliate and cripple the English authority at sea.

Resources

Queen Anne’s Revenge.

Undead crews and ghost ships.

Fear and reputation.

Notable impacts as goals completed

Major English ports fall into chaos (martial law, burned docks, naval retreat).

English Naval presence reduces.

Obstacles

Royal Navy patrols.

Pirate captains unwilling to fight England directly.

English spies inside pirate ports.

2) Control the ASH trade

Weaponise ASH as leverage and corruption tool.

Resources

Unending ASH Reserves.

Contact with Governor Claude Barlette.

Smuggler Networks from his old life.

Notable impacts as goals completed

ASH price doubles.

Obstacles

Pirates!

3) Crown himself king of the Dark Caribbean

Resources

Undead Crews.

Fear & Reputation.

Abyssal Necromancy.

Notable impacts as goals completed

Nassau-style pirate councils dissolve or are slaughtered.

Pirate captains must swear loyalty or be hunted.

Obstacles

Charismatic rival captains.

Internal dissent from living allies.

Conclusion

Let me know in the comments if you want me to do a real history and lore for any of the other factions!

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running! If you’ve still got some time to kill, Perhaps I can persuade you to click through below to another one of my other posts?

Catch you laters, alligators.

Who Was Blackbeard? Pirate Borg World Building

I’ve bit the bullet and and I’ve agreed to run a couple of one shots for Pirate Borg. One’s for my regular group, and the other is a group of people I met in a local online community. This is all well and good, but it got me thinking more about Pirate Borg lore.

By JimmiWazEre

Avast, ye scurvy opinionated tabletop gaming chap

TL;DR:

Blackbeard’s career lasted barely two years, but in that time he captured a slave ship, blockaded Charleston, outplayed governors, accepted a royal pardon, and died in a last stand at Ocracoke.

Introduction

I’ve bitten the bullet and and I’ve agreed to run a couple of one shots for Pirate Borg. One’s for my regular group, and the other is a group of people I met in a local online community. This is all well and good, but it got me thinking more about Pirate Borg lore.

Not a problem, when it comes to thinking about things - pirates are definitely up there for me as hot property.

So in this post I’m going to cover the known real history of Blackbeard, complete with some reasonable assumptions. Next time, I’ll take that timeline and append my Pirate Borg nonsense to it so you can see how this all fits in with the Dark Caribbean setting.

Enjoy.

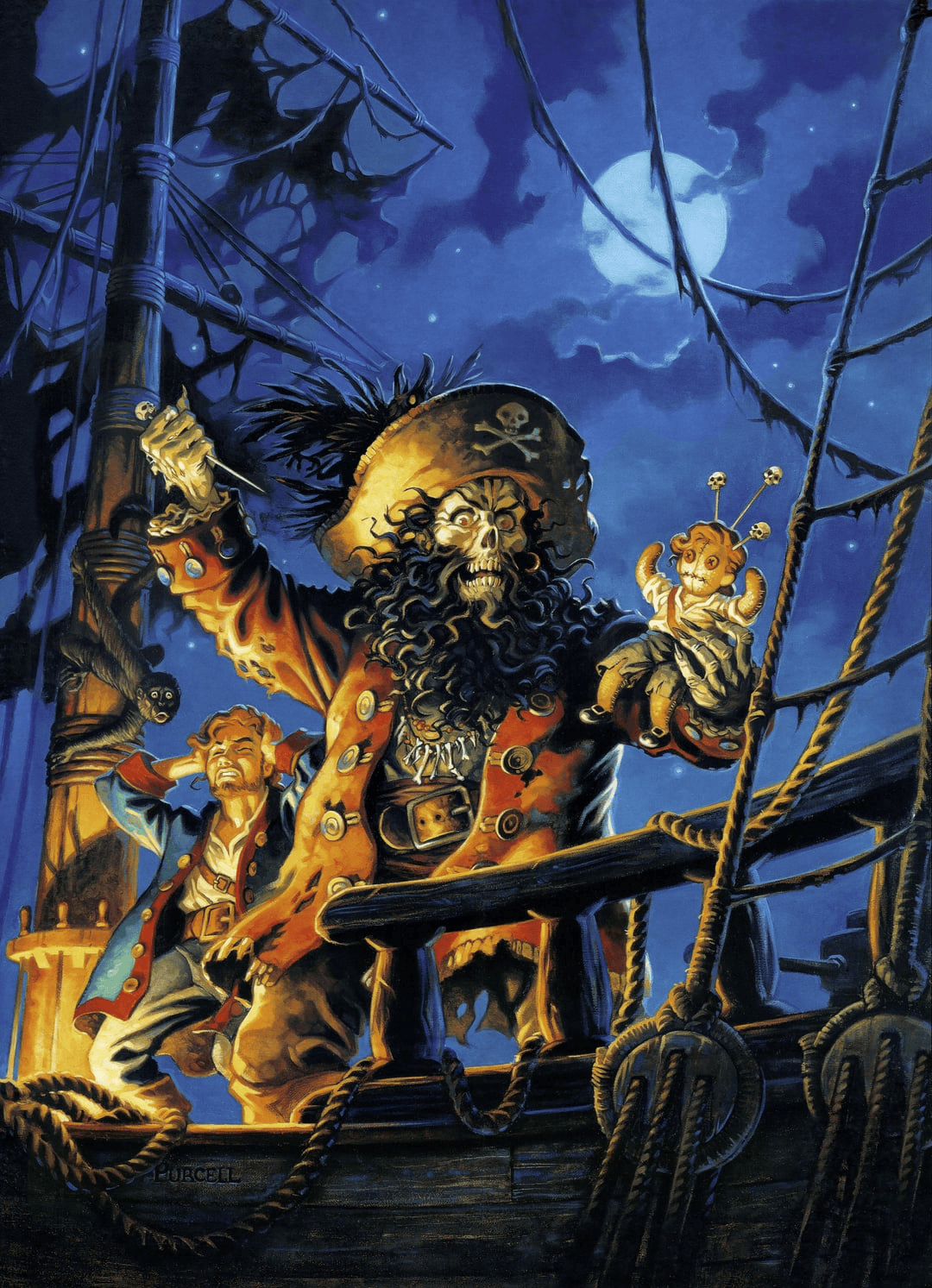

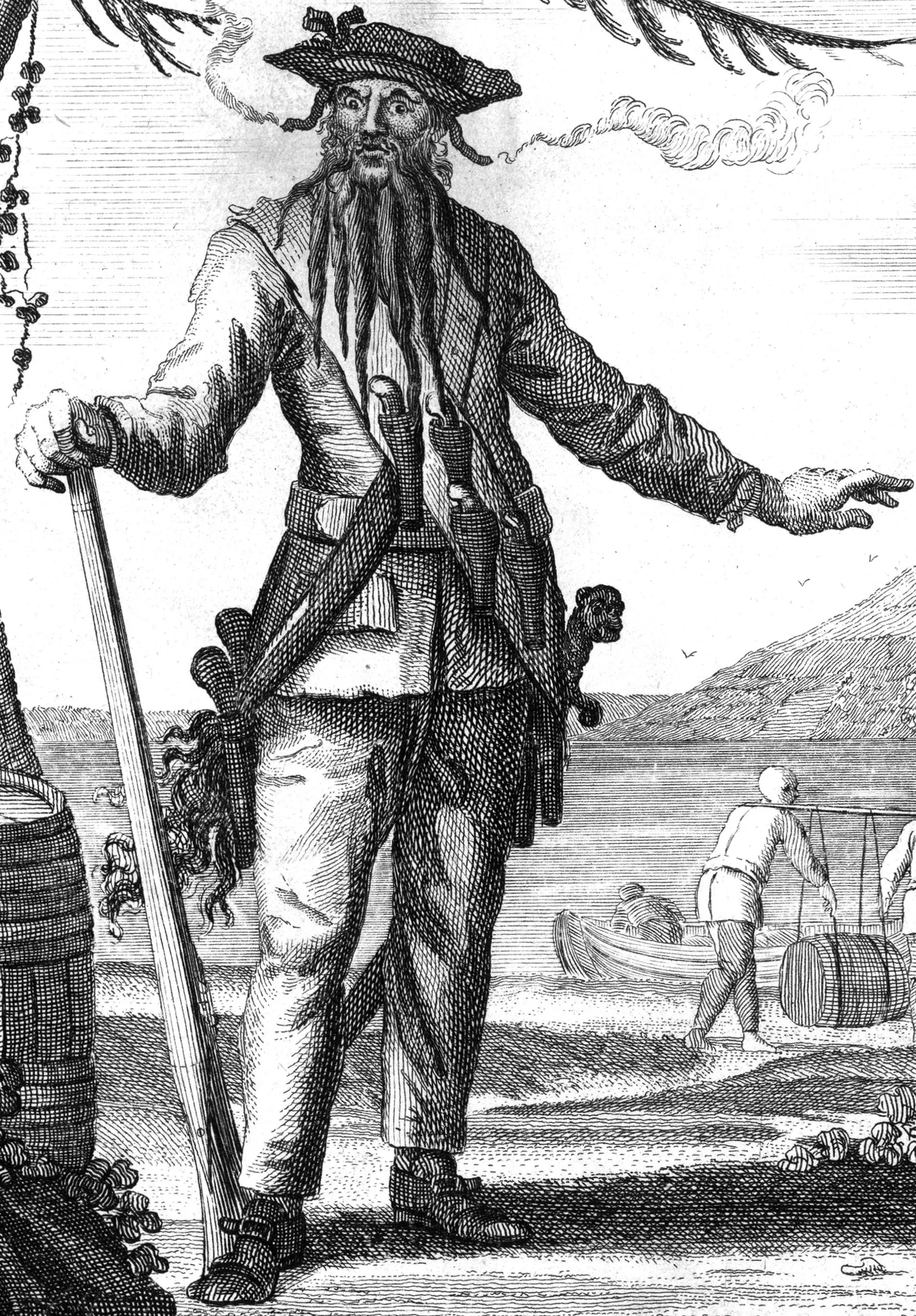

The Real History of Blackbeard

Surprisingly, there’s not actually much known about the life of Blackbeard, and much of his early life is genuinely unknown, whilst that which is well documented only covers his brief but legendary career during the golden age of piracy.

Early, And Somewhat Sketchy ‘Facts’

Real Name

The first question we have to ask is who actually was this dude? Well, based on surviving legal documents, maritime reports, and inter-colony correspondences; Blackbeard’s actual name was Edward Thatch. Or maybe Edward Teach. (Or maybe Barry).

Hang on Jimmi, we’ve only just started - why are we uncertain already? Well chum, because we don’t actually have any recorded signature from Blackbeard, and all the records are from some third party writing about him, and he didn’t exactly go around the place signing up for membership cards and leaving a nice first hand paper trail for us. Rather, he’d have introduced himself verbally. Probably whilst on the deck of a ship on a windy day with some juicily broad South Western British accent, delivered to people who were far too terrified to be paying too much attention to detail.

Under those circumstances it’d be easy for someone to mishear his name. Not to mention that the common sailors he’d have been talking to were unlikely to speak English fluently, or be literate. And then even, the semi literate ones who did hear his name correctly, and could understand him - there’s every chance that they wrote his name out phonetically, and spelled it wrong, or that the reporting Clerks did so later on after hearing weeks old verbal accounts.

And it gets even more unreliable, I’m afraid. Typically Pirates don’t give away their real names because they didn’t want to bring trouble for Mummy and Daddy Blackbeard back at home. So both Thatch and Teach - it’s entirely possible that Blackbeard used them both as aliases, and maybe his real name was Barry. But - I don’t like that. It’s a dead end. So to sound informed, I’ll just acknowledge that it’s a possibility, and then move forward with the historical best guesses. ‘Blackbeard’ was already his alias, and it was cooler than a penguin’s arse - he didn’t need any more.

Place of Birth

In a 1724 book called “A General History of the Pyrates” is published by someone calling themselves ‘Captain Charles Johnson’. Alas, this was a pen name, and the real author’s name is again, hotly debated. Anyway, the book profiles various 18th century pirates, including Blackbeard, and it names him as being from the major Atlantic port town of Bristol, UK. If we skip forwards to today, historians have found records of the surname “Thatch” appearing in British parish records around 1680. “Teach” is nowhere to be seen.

This all fits: the name, and a link to a maritime location. Then the date; circa 1680 puts him around his thirties and forties which is reasonable. I’m happy so far.

Pre-Piracy Career

This part is almost entirely speculative. You see, Blackbeard was renowned as a skilled pirate. That’s a command of sailing, of combat, and psychological intimidation. It therefore makes sense that he picked these skills up somewhere in advance of his piracy career, and the most obvious place to do so would have been through operating as a Caribbean privateer in the era 1701 - 1714.

Privateers were seamen operating with the explicit written permission of the state to do pirate things, as long as they were only acting against the state’s enemies. At this time, that was the Spanish and the French as a result of the War of Spanish Succession.

Interestingly though, we’ve got two ingredients for our next piece of educated speculation. The first: Blackbeard was a skilled pirate - as above, and the second: “Edward Thatch/Teach” is not mentioned in any records as being a captain on any privateering expedition. If he was a captain, he absolutely would have been mentioned because these are official letters of marque.

Logically then, if we accept that he indeed gained his seamanship experience as a privateer sometime between 1701 and 1714 - that then likely places him as mid-tier crew. Senior enough to get command and tactical experience, but not senior enough for anyone to write his name down.

It’s Piracy Time!

Mentorship under Benjamin Hornigold

In 1716, A General History of Pyrates places Blackbeard in the ex-British port town of Nassau, New Providence (our first real solid historical record of Mr. B.Beard actually). There he serves under the legendary pirate captain; Benjamin Hornigold who obviously sees enough in him to eventually bequeath him command of a small sloop by the start of 1717.

The name of the sloop is lost to history, and Blackbeard’s role as captain here is still subordinate to Hornigold, whom you might consider to be a pirate admiral at this stage. However, the partnership was fruitful and they captured ships off Cuba, Hispaniola, and the Bahamas trade routes.

Given he was in command of a sloop, we can deduce that Blackbeard’s role in these escapades was to utilise the speed of his vessel for intercepting lightly armed ships and taking shock-style boarding actions rather than trading broadside cannon fire. An active raider, if you like - rather than a commanding overseer.

Glorious Piratey Independence

By mid 1717 however, Hornigold is starting to lose the confidence of his crew. You see, Hornigold would describe himself as a British patriot, and as such, refused to engage against British vessels. His crew though, they were distinctly less picky and eager to crack on, and this friction was starting to show. In fact Hornigold’s waning authority might have been a key factor in Blackbeard’s bold move that came next. In November 1717 Blackbeard (still in his sloop, but probably with additional ships in tow) intercepted a large French slave ship off the coast of Martinique called La Concorde.

Now, La Concorde was chonky my dudes. ‘Baby got back’. 200+ tons of it in fact, and built for Atlantic crossings. Indeed, on this occasion it was at the tail end of such a voyage and was carrying West African slaves to Martinique. It was heavily crewed, but was by no means a ship kitted out for war.

According to French reports, the crew was already weakened by dysentery and fever and were probably very much looking forward to making port soon. That’s when Blackbeard took chase. With his nimbler sloop he was able to close the distance rapidly.

There ensued a brief engagement which involved limited cannon fire and musket volleys. La Concorde was not heavily armed at all, and the reports indicate that the French Captain, Pierre Dosset surrendered quickly, which is a testament to Blackbeard’s famously intimidating tactics.

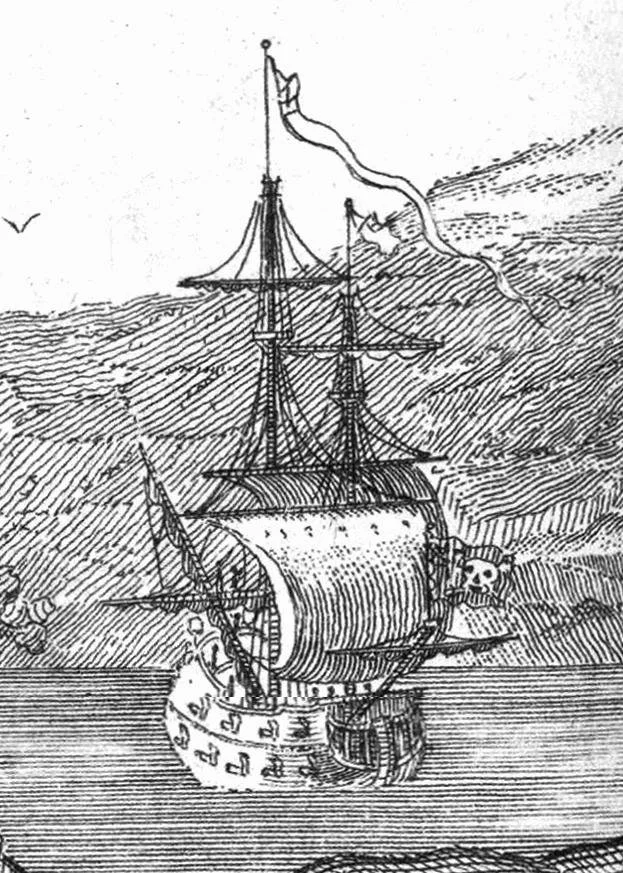

The Queen Anne’s Revenge

Alrighty - now we’re cooking! Blackbeard claimed La Concorde for himself, and fitted it out with forty cannon to make it one of the beefiest pirate ships of the era. This thing was a major escalation in power projection for him, and enabled him to take on larger merchant vessels.

He chose to rename La Concorde to Queen Anne’s Revenge (QAR), and as is sadly typical by now - we don’t have concrete proof as to why. Though we can infer it; Queen Anne was the British Monarch from 1702 - 1714, and her reign ending coincided with the end of privateering work which was something of a sore spot for many pirates, as it fundamentally took their jobs away and forced them into true crime. It’s likely that the name ‘Queen Anne’s Revenge’ was both a nostalgic nod to those privateering years and likely an ‘up yours’ to King George the 1st, the first British monarch from the controversial house of Hanover.

Needless to say, we’ve entered the period now where Blackbeard is gaining fame and fortune, using his pirate armada to terrorise the Caribbean seas. Tactically speaking, Blackbeard wasn’t known to be gratuitously murderous, but rather he carefully cultivated an image and reputation of terror. Preferring his prey to voluntarily give up without a fight out of sheer terror, than to put himself at unnecessary risk. Having a massive ship that everyone’s scared of certainly helps in that regard!

Peak Piracy

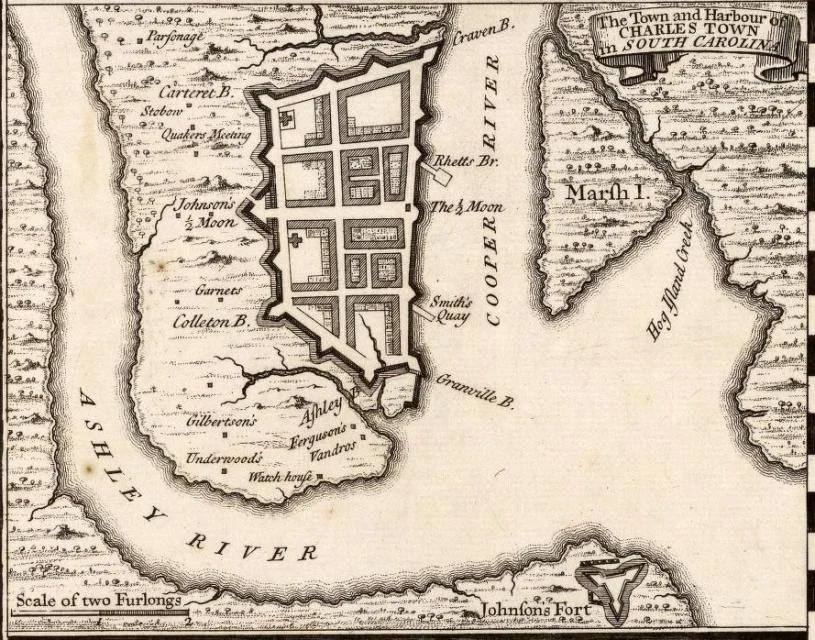

The Charleston Blockade

On 22nd May 1718 Blackbeard pulls off his most daring move to date. Aware that there’s no navy presence in the vicinity, Blackbeard takes the QAR alongside 3 other ships and probably more than 200 men, and parks them outside the harbour at Charleston, South Carolina. Over the next week he proceeds to capture around 10 vessels, and stop all incoming and outgoing traffic. The ships he caught were stripped of all valuables, including prominent passengers such as members of the provincial council, and well connected colonists.

He then issues a demand to Governor Robert Johnson. Not for gold, not for crew, weapons, or more ships. No, Blackbeard demands a chest of medical supplies. You see the Caribbean in the 18th century was a hotbed of disease, and nowhere more so than the tight confines of a boat - dysentery, syphilis, fever, all manner of tropical diseases and Blackbeard is not immune to this.

Unfortunately for Johnson, he’s got no real choice but to comply - the blockade is causing severe economic damage and political embarrassment. Isolated, and with the British Navy stretched too thin, he’s in no position to address the situation militarily. Consequently, the demands are met and the chest is dispatched. Blackbeard disburdens them of their valuables, then releases the last of his hostages and peacefully sails away having metaphorically pulled Johnson’s pants down, and blown a raspberry at him for all to see.

The End Times

The King’s Pardon

Not long after Charleston, in June 1718 at Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina - Blackbeard heads to shore to careen his ships. Unfortunately, or maybe intentionally, he manages to run both QAR and one of his support sloops called The Adventure aground against a sandbar.

The incident is fatal to QAR, the main sail is cracked, and many timbers are shattered. In response, he transfers all valuables onto a smaller vessel and leaves the scene - abandoning both the wreckage and a large proportion of his crew behind.

There is some debate about whether this was intentional. Whilst blockading Charleston, Blackbeard learns that the British have dispatched a fleet of man-o-war led by Woodes Rogers to deal with the pirate problem in the Caribbean, and not only does the QAR draw unwanted attention, it’s no match for the might of the British Navy. In addition to this, evidence suggests that the QAR was severely damaged prior to the grounding, and in combination with having a massive crew to upkeep and share spoils with, Blackbeard may have decided it was best to kill two birds with one stone and simply abandon them.

Whatever the cause of the grounding, not long after and having heard that the King’s Pardon was being offered to all pirates who surrendered before the 5th September 1718, Blackbeard and his collaborator Stede Bonnet decide that this is probably a good time to bow out. Of course, Bonnet is sent first alone to North Carolina’s Governor Charles Eden, so that Blackbeard can be satisfied that the offer is genuine!

Indeed it is, and both pirates take the King’s Pardon and vow to end their piratical ways. And Blackbeard does, for a couple of months at least. He settled in a town called Bath, and generally plodded around the place for July and August, before Governor Eden presented Blackbeard with a letter of marque granting him the right to take up privateering again in his remaining sloop; Adventure. Shortly after that, temptation must have proved too great as Blackbeard is right back at it.

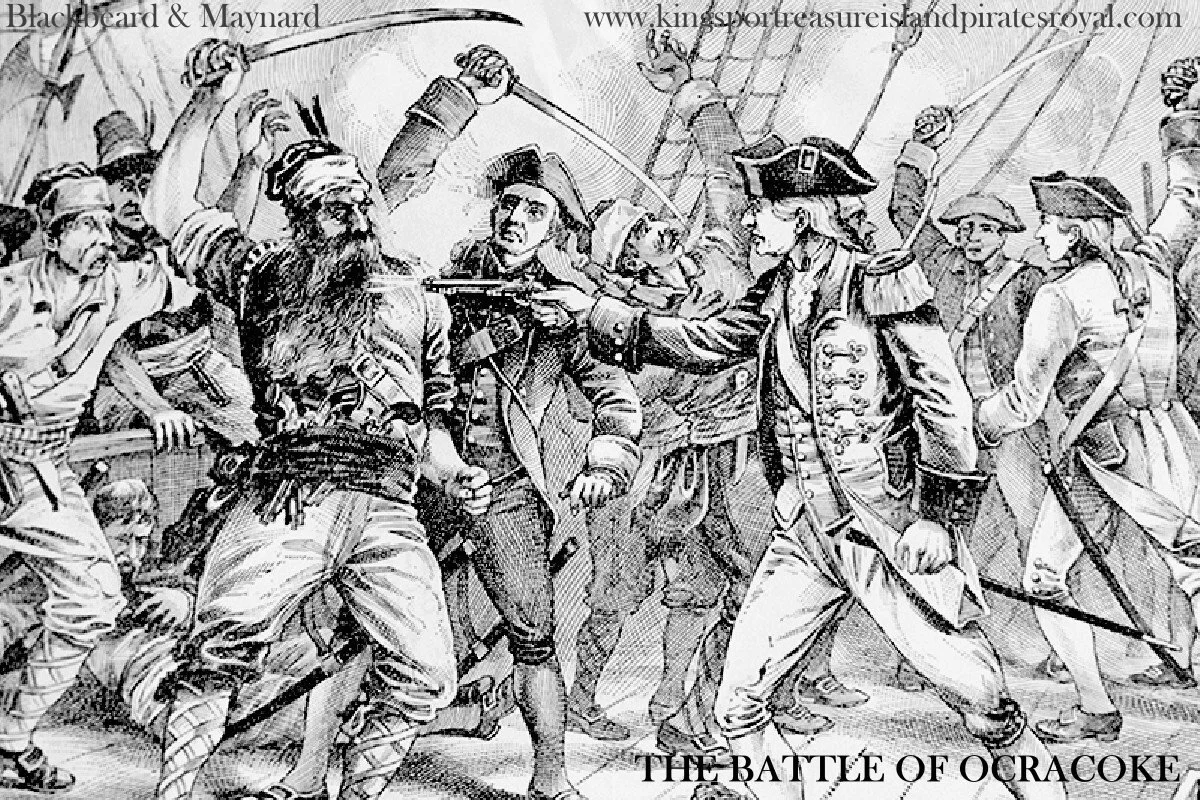

Death At Ocracoke

The Governor of Virginia is a fellow called Alexander Spotswood, and he is most dischuffed that Governor Eden has granted Blackbeard his pardon, believing that the freebooter is taking liberties. Indeed, this dischuffedness is further compounded when he learns that Blackbeard has moored up off Ocracoke island, North Carolina and taken to partying with well known pirates such as Charles Vane with absolute impunity.

Spotswood decides to take matters into his own hands, and personally finances two sloops (Jane and Ranger) lead by Lieutenant Robert Maynard to bring Blackbeard to justice. They find him anchored on the inner side of Ocracoke, only 25 men carousing aboard the Adventure and decide to remain hidden, waiting until morning when they could take advantage of the pirates inevitable hungover state, and better navigate the shallows in the daylight.

At daybreak on 22nd November 1718, Maynard struck! Not for nought though was Blackbeard the most reputed pirate of his time, and after a devastating broadside from the Adventure, Maynard had lost a third of his forces.

Now, in poker there’s a phrase “You have to play the hand you’re dealt” and Maynard did this brilliantly here. He orders his remaining men to split, a handful remain with him up top and the remainder hide below deck to give Blackbeard the impression that there’s few remaining. The pirate takes the bait! He boards the Jane and engages against Maynard’s visible crew in hand to hand combat. At this time, the hidden crew below deck burst forwards and surround Blackbeard’s men, and a bloody battle ensues.

It is reported that Blackbeard took 20 cuts from bladed weapons, and 5 wounds from small arms fire before he eventually fell. Maybe he felt that he needed to make sure then, as Maynard decapitated his corpse and cast Blackbeard’s headless body into the sea. The head was then strung up on display as he made sail back to Virginia where it then found a new home atop a pike at Chesapeake Bay to act as a warning to other pirates.

Sometime later it was removed, and history has forgotten where it ended up.

Blackbeard Timeline

circa 1680 | Born in Bristol as Edward Thatch

circa 1701-1714 | Suspected Caribbean privateering

Late 1716 | First recorded piracy as mentee under Benjamin Hornigold

Nov 1717 | Captures La Concorde and renames her Queen Anne’s Revenge

1717 - 1718 | Generally kicks ass and takes names

May 1718 | Blockade at Charleston

Jun 1718 | Loses Queen Anne’s Revenge running aground at Beaufort inlet

Mid 1718 | Accepts Kings Pardon from Governor Eden

Jul - Aug 1718 | Plans return to piracy

Nov 1718 | Slain at Ocracoke Island by Robert Maynard

Conclusion

What a dude! It’s amazing how he became the world’s most famous pirate, even to this day whilst only really operating for about two years. If any of you are history buffs, feel free to comment below anything you think that I’ve missed or got wrong. I promise I’ll read them all.

Also whilst I’ve got you, I want to apologise for the delay in posts at the minute. My laptop broke in January and I’m battling the retailer to accept responsibility for it, so I’m sharing a PC with Mrs. WazEre. Additionally, I’ve managed to pick up a nasty disease which has knocked me out a bit. But all’s being well, I’m hoping to compliment this piece soon with my own fiction regarding how I’m baking Blackbeard into my Pirate Borg world building.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running! If you’ve still got some time to kill, Perhaps I can persuade you to click through below to another one of my other posts?

Catch you laters, alligators.

How To Run A Dungeon - Fixing The Lost Mine of Phandelver

Here’s the problem, if you grew up in the 90’s or later, and have only ever played 5e - it’s likely that your only detailed point of reference for what a dungeon experience is like comes from video games - maybe something like Zelda (Ocarina of Time - best game ever made. Fight me!) The issue here is that they teach the player that a dungeon is this linear place, to be solved in a set way, with battles in predefined places.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap, who’s having to write this on his wife’s laptop because his broke :(

TL;DR:

Lost Mine of Phandelver gives you dungeons but no guidance on how to run them well. Good dungeon play needs urgency, resource pressure, meaningful time tracking, and dynamic encounters. This post breaks down classic and modern dungeon crawl procedures; from Justin Alexander’s traditional dungeon turns, to The Angry GM’s Tension Pool, Goblin Punch’s Underclock, and Dungeon Masterpiece’s encounter tables — and then shows how to use them to make Phandelver’s dungeons tense, reactive, and actually fun to run.

Introduction

Are you trying to run Lost Mine of Phandelver? I ran it recently. Have you noticed how (despite being a ‘starter set’) it does absolutely nothing to teach you how to run a dungeon? Bummer right?! Literally - there’s arguably five dungeons in this module, and it doesn’t show you how to run them at all. In fact, the closest it comes is the final dungeon where it even acknowledges how boring it’s going to be, and weakly suggests rolling for random encounters on a d20 table as and when you feel it’s appropriate.

Do better, Lizards-Ate-My-Toast.

You see, if you don’t know what you’re doing with dungeons, they can very easily turn into this very boring, very samey experience, with your players meticulously checking every tile for traps as they move from room to room, occasionally interrupting monsters that have apparently been sat there for an eternity - waiting to meet the PCs! Meanwhile the PCs have been long resting every couple of encounters to make sure they’re at maximum power all the time. And my God, I’m bored just thinking about it!

The chief cause of this dry experience is that there's no urgency or risk management. So how do you get that, I hear you ask? Damned fine question if I may say so myself, pat yourself on the back. You my friend, should read on, because unless you’re particularly looking for a simple linear gauntlet of pre-defined encounters, you probably need a “Dungeon Crawl Procedure”.

What In The Name Of Sweet baby Jeebus Is A Dungeon Crawl?

Here’s the problem, if you grew up in the 90’s or later, and have only ever played 5e - it’s likely that your only detailed point of reference for what a dungeon experience is like comes from video games - maybe something like Zelda (Ocarina of Time - best game ever made. Fight me!) The issue here is that they teach the player that a dungeon is this linear place, to be solved in a set way, with battles in predefined places. It works in a videogame because of the spectacle and hand eye skill involved.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t translate well to TTRPGs I’m afraid and these games bear little resemblance to what a D&D dungeon is supposed to be.

The fact that people try to emulate these video game experiences is why they fall flat at the table. It’s why your players probably don’t like dungeons, and it’s why you probably don’t like running them.

So, What’s missing?

To run a better dungeon, I advocate for the following components:

There should be no predefined method or route for ‘completing’ the dungeon. The player’s motivations and methods should be their own, and you should expect them to shift as they learn new things and as the situation inside the dungeon develops.

The dungeon should be punishing, and it should be a place that drains resources which cannot be easily replenished whilst the characters remain inside. This could be HP, or light, or spell slots, or rations, or more likely - some combination thereof.

The dungeon should be dynamic. It should move and breathe, and be both proactive and reactive in response the player character’s trespass. There should be opportunities within for all the major pillars of play - combat, social, and exploration.

Time should matter, it should be tracked carefully. Time affects your resources, and the position of dungeon inhabitants, and wasteful players should feel all these factors as keenly as a pin in their arm.

Which brings us nicely onto the “how” part of this post. Well my dudes, you have options. You see, it’s been a hot minute since the 1970’s and quite a few people have stepped up to the mark and developed processes for running dungeons. Here’s a handful of them:

Dungeon Crawl Processes

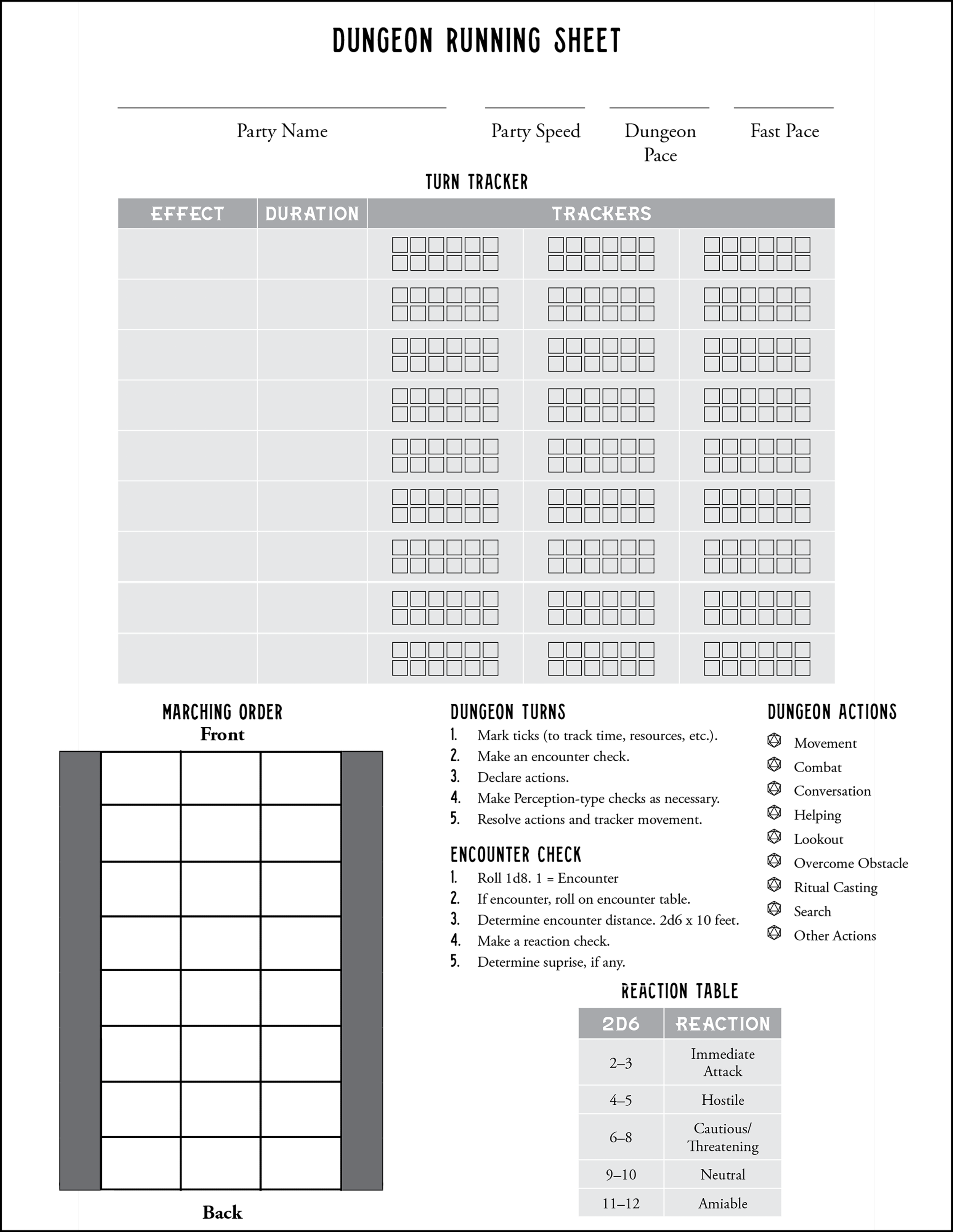

Justin Alexander - So You Want To Be A Game Master

In his book, Alexander explains a very traditional style. It’s a method that’s as old as the hobby itself, and it sets the fundamentals of most of the methods to follow - tracking time, resources, generating improvised encounters, and the concept of a Dungeon Crawl as a minigame within D&D as legitimate as combat.

Marching Order

Getting players to declare a set marching order for the party up front solves a lot of hassles later on. As GM, now you know which characters are likely to trigger/spot traps, and which are likely to be picked off from the rear.

Dungeon Actions

After Marching Order, the next thing to define are the Dungeon Actions, these are not dissimilar in concept to the actions you can take in combat. Don’t read these as an absolute list, but rather as some common actions, which you can improvise upon as required.

This list includes, but is not limited to the following:

Move carefully (a snail’s pace. default movement speed to reflect the extreme caution of PCs moving through this pitch black, dangerous, scary environment).

Move fast (for when the PCs throw caution to the wind out of absolute necessity, or if they’re backtracking over a recently explored space).

Unlock a door.

Disarm a trap.

Investigate an area (getting more detail about some room feature than has been vaguely called out in the room overview).

Look for secret architecture (hidden doors, traps, pits).

Keeping watch (reducing/removing chance of being taken by surprise).

Casting a ritual spell.

Something else (talking to an NPC, loading your pockets with treasure, helping another PC, lighting a torch etc).

The idea here is that each player does one of these things per Dungeon Turn. Sometimes your players might want to do something so insignificant that you rule that they can have another action. This is fine. Trust your gut.

Dungeon Turn

This is an intentionally loosely defined amount of time - usually ten minutes (this is because ten plays nicely with many timed effects in D&D which are usually roundly divisible by this figure). Don’t sweat the precise granularity of it vs the actions taken in the Dungeon Turn, it requires not overthinking it in order to be effective.

Once the Dungeon Turn ends, the GM performs a bit of bookkeeping on their Dungeon Running Sheet. Justin Alexander features one on his website for you to print out and use:

The idea is that you record each ongoing item or spell effects duration per row, and then for each Dungeon Turn mark a tick in each row (all rows should read the same number of ticks in Alexander’s version, other designs may vary). When a given duration is met, that effect ends.

Whilst Alexander advocates doing this behind the scenes and making it feel less clunky and mechanically like a boardgame, other D&D scholars disagree. Dadi on Mystic Arts describes this process, but instead leans into the idea that the players should be aware of what’s going on behind the scenes to better inform their decisions, and thus debates.

You do you.

Regardless - there is one final step the GM takes as part of their bookkeeping.

Random Encounters

These are so important, and so many GMs are terrified of them in case they “ruin their story”. I say; it’s time to cowboy the chuff up, get comfortable with improv, and embrace the dice my friend! Seriously, stop worrying so much about game balance, and just trust your players to make the right choices to get out of whatever peril the dice serve up for them :)

Random encounters are valuable because they make your dungeon feel alive and dynamic. Rather than the players feeling safe that they can only encounter creatures as they travel to a new area, now, the creatures can come to them. Alexander recommends the following method:

Once you’ve done all your Dungeon Turn bookkeeping, roll a d8. A result of one means that an encounter will occur.

Roll on your pre-prepared Dungeon Encounter table to decide which encounter it will be.

Determine how far away the encounter is by rolling 2d6 x 10 feet.

Unless it’s obvious, make a 2d6 reaction check to determine the attitude of the creatures you’ve encountered. Not all encounters have to be fights.

Determine if one group is surprised by the other, usually Stealth vs Perception checks. Any players taking the ‘keep watch’ Dungeon Action infer a better probability of success here.

The Angry GM - The Tension Pool

One problem with the traditional method described by Alexander is that the only sense of increasing dread comes from resource drain. The odds of an actual encounter remain static, and this effects the psychology of the group if you’re trying to foster a sense of ever creeping doom!

Responding to this shortfall, the Angry GM has a nifty little replacement for traditional random encounter checks called the Tension Pool and it all starts with a glass bowl.

Each Dungeon turn, toss a d6 into the glass bowl (AKA the Tension Pool). This should be visible to all the players. Then:

Each time during a dungeon turn that a PC does something risky or noisy, you roll any dice in the Tension Pool. Results of six prompt a roll on your pre-prepared encounter table.

Each time the Tension Pool fills up with 6d6, roll all the dice in the Pool as above to check for encounters, and then reset the pool to zero.

This is pretty cool, two things are happening:

We’re tracking the passage of time, with a dice in the pool representing a dungeon turn.

The likelihood of a random encounter is visibly impacted by the passage of time and the actions of your players.

That said, not everyone agrees that this is enough, I reckon that with a small modification, you could also use this to abstractly track effects using different colour dice of different denominations. For example, if someone lights a torch, toss in a d8 (or whatever seems right - I’ve not play tested this). The d8 will never trigger an encounter check like a d6 does, but each time the pool is rolled, that d8 might come up with an eight, and if it does - the torch is snuffed out (and the d8 is removed).

This way that’s less stuff to track on a piece of paper, and we’ve also now baked in variance on item and spell effect durations - if that torch goes out, maybe it was a gust of wind? If a spell effect ends, maybe the caster tripped on a flagstone and lost concentration?

Goblin Punch - The Underclock

Arnold K over at Goblin Punch has an entirely different method for using random encounters to build tension. He calls it the Underclock and it works like this:

Grab a d20, a nice big one. Or use a piece of paper, or a paper dial, or whatever you have that can track to 20. This is the Underclock, keep it out in the open so the players can see it.

Starting from 20, each Dungeon Turn the GM rolls a d6 and subtracts the result from the Underclock value.

Results of six on the d6 explode (this means you roll an additional d6).

When the Underclock hits less than zero it triggers an encounter on your random encounter table. At zero exactly, the clock resets to three instead.

If the Underclock ever reads three, a foreshadowing event occurs and the PCs learn a clue about the nature of the impending encounter (naturally, you’ll have to roll the random encounter at that point for your own reference).

The nice thing here is the players are more informed (but not perfectly so) about when an encounter is due. You can represent this as them hearing noises, or ‘spidey sense’, or whatever works for you.

This forewarning means that the players have another interesting decision to make - do they press on, do they try to hide, or do they prepare an ambush instead?

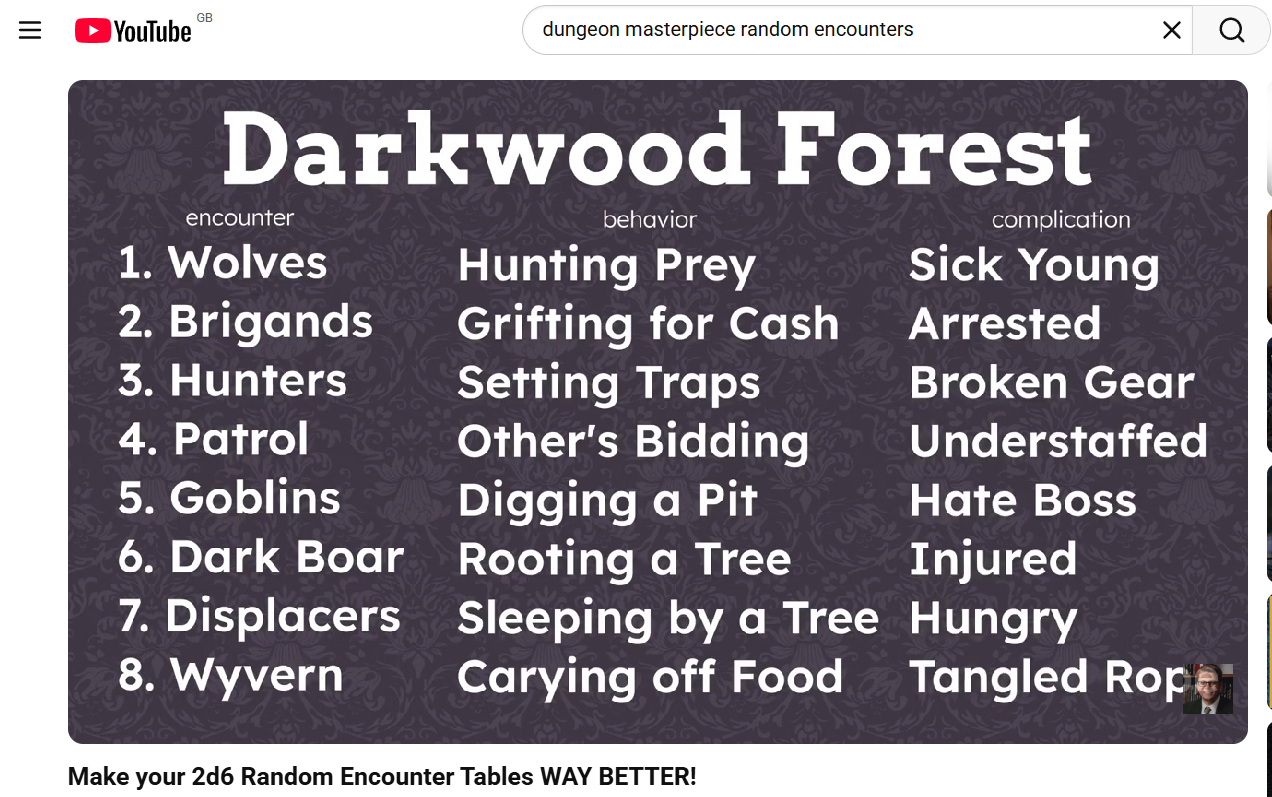

Dungeon Masterpiece - Random Encounter Tables

Baron de Ropp at Dungeon Masterpiece makes an excellent point regarding Random Encounter Tables.

Traditionally, they’re either single die table of possible encounters, or they’re a multi-dice table, which introduces a bell curve only the range of outcomes. Then on top of that you layer distance and reaction.

De Ropp highlights that this structure alone does not do anything to weave a larger narrative together, nor is it scalable, nor does it do much to help the GM to come up with a unique yarn to spin about the specific encounter.

To resolve this, he has a number of tricks:

If you have quests and rumours planned out - seed these into your random encounters. That pack of wolves you just defeated, maybe one of them had a golden arrow buried in its flank. Who made the arrow? Perhaps there’s someone in the woods that specialises in such trinkets?

If your table contains six entries, corresponding to a d6, why not add two more entries to it. Order the tables by difficulty, and then as your players advance in skill, add +1 or +2 to their dice result to weigh the results in the favour of more difficult encounters.

This one’s the real juice. De Ropp suggests adding two more columns to your random encounter table. Behaviour and Complication. You fill these in on a per row basis in a way that makes total sense for that given row. For example - Wolves. The behaviour might be “Hunting Prey” and their complication might be “Their pups are sick”. Here’s the clever bit - you roll three times on the random encounter table, generating a potentially different row per column. You might come up with “Goblins”, “Grifting for Cash”, “Their pups are sick”. This is your improv prompt for the scene, and by combining the elements from different rows, you’ll come up with some really unique encounters.

I’m a big fan of building Encounter Tables this way, and aside from the small amount of extra prep work they take - there’s not really much in the way of downside that I recognise.

Conclusion

So there you go. Whether it’s the Goblin Caves, Redbrand Hideout, or Wave Echo Cave - you’ve now got a detailed set of options for running these dungeons in a way that’s time tested and true. Let me know below the line if you have any other tips for people looking to improve the way that they run dungeons.

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running! If you’ve still got some time to kill, Perhaps I can persuade you to click through below to another one of my other posts?

Catch you laters, alligators.

GM Burnout - When You Just Can’t Anymore

GM Burnout is a unique form of creative burnout, where a lack of inspiration and joy from the creative aspects combines with the drain of the relational and performance demands of the role.

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated, and ‘whelmed’ tabletop gaming chap

TL;DR:

GM burnout isn’t laziness or loss of passion, it’s a signal that something in how you’re running games is draining you. By identifying the real cause, whether it’s workload, values conflict, social pressure, or lack of reward, you can take focused steps like resting, changing systems or structure, sharing responsibility with players, and reconnecting with the parts of GMing you actually enjoy.

What Is GM Burnout?

Are you feeling a bit spent, old chum? Tired of running D&D? Can’t bring yourself to actually think about your upcoming game, or perhaps you’re simply filled with ‘meh’ about the prospect of running tonight’s session? Don’t judge yourself too harshly - this doesn’t mean you’re lazy, or that you’ve gone off TTRPGs. You might be suffering from GM burnout.

GM Burnout is a unique form of creative burnout, where a lack of inspiration and joy from the creative aspects combines with the drain of the relational and performance demands of the role. So where a visual artist might be blocked or not be feeling creatively inspired anymore, a GM has that too with their lore and maps etc, plus the weight of managing group dynamics, schedules, and the ‘always on’ energy of running sessions.

As above, it’s important to recognise that burnout isn’t laziness. It’s a vital communication from your brain, so listen to it. It simply means you’ve likely been burning the candle at both ends to the extent that you’re emotionally, socially and/or creatively depleted. It doesn’t mean that you’ve fallen out of love with the game. In fact the opposite is true, you’ve such strong love for what you do, that you’ve poured too much of yourself into it without stopping to refill your tank.

Let’s top you up shall we?

Where Does GM Burnout Come From?

You have to start this process logically. So step one is to identify the cause that fits with YOU. ‘The 5 Whys’ (Serrat (2009)) can be a useful tool of self discovery if you’re struggling to put your finger on it. Simply ask yourself “Why?” five times, starting with your answer to “Why am I burnt out?”, and then for each subsequent answer in turn. The idea is that through this interrogation, if you’ve been honest, you’ll start at some vague, surface level thing that you can easily identify, and you’ll end up at the creamy centre of your problem. The cream is good my friend.

Once you’ve done that check this out: Referencing Drs. Leiter and Maslach, Davies (2013) points to major occupational burnout causes below - several of these clearly resonate with game mastery, do any of these fit with your ‘5 Whys’ conclusions? (If not, tell me in the comments below, I promise I read every one).

Work Overload

This one is easy to spot. It might be too much prep, like trying to build an entire world with all its moving parts, or maybe tying yourself in knots trying to maintain a coherent ‘story’.

That said, it could also just as easily be that you’re struggling with heavy improvisations during sessions and maybe they’re too long, or you don’t get enough time between them to rest.

Values Conflict

If you’re only ever running a particular type of game and it no longer tickles your pickle, that can suck the life out of the hobby for you. With the amount of people that only ever play high fantasy D&D - this one doesn’t take too much effort to imagine.

To greater or lesser extents, it’s rare that we thrive on doing the same thing over and over again, and variety is the spice of life.

Lack of Control

When you’ve got an idea on the type of game you want to run and the direction it takes, but the players have taken it somewhere else entirely. Not specifically in terms of “plot direction”, but tonally. Maybe you wanted to build a sandbox filled with discovery and wonder, but now you're writing plot hooks for a moustache-twirling villain because your players demanded a classic BBEG.

Over time, this mismatch between your intentions and the game’s direction can leave you feeling disconnected from your own work.

Community Breakdown

In TTRPG terms, this is where we see problems with the social dynamics among all the players. If you’ve got a guy who always creates trouble for the group and he’s been allowed to continue, your enthusiasm for the game is going to be well and truly tainted by that. Especially if everyone just leaves it to you to be the adult in the room all the time.

Insufficient Reward

Do you feel unappreciated? Do your players turn up unprepared? All you ever hear from them is complaints about one thing or another? Do they take the effort to ever show their gratitude?

When you get the wrong answers to these questions, it’s easy to start asking yourself: “Why do I bother?”

Additionally, Tyler (2025) adds to our list the impacts of deadlines, pressure, and work-life balance:

Deadlines and Pressure

Constantly feeling like you’ve got to raise your game and provide increasingly ‘better’ experiences for your players, or that knowledge that every single week you’ve got to have another session up and ready to go. That makes your ideas forced, and leaves little room to enjoy the creative process.

How to make a hobby feel like ‘work’ 101.

Work-Life Balance

Quite simply, you may just have too many different obligations going on right now. When we feel this way, it’s easy to become paralysed and avoidant. Check your to-do list, do you have a bunch of things that other people are counting on you for, competing for your attention right now? If so, you’re overwhelmed.

(Side note, you hear about people being overwhelmed and underwhelmed all the time. Does that mean that the desirable state is simply to be ‘whelmed’? - Q) “How are you feeling today?” A) “Oh I’m fairly whelmed, thank you for asking”. Language is stupid.)

What To Do About GM Burnout

That’s a pretty good amount of potential causes up there by anyone’s reckoning, so if you identify with one or more of them, even though it might be obvious what the solution is, these are some additional areas where you can make changes to feel more like your old self again.

It’s important to note that these will not all be applicable, so use your noggin and cherry pick the ones that align best to the cause of your malaise!

Take an Intentional Break

It’s older advice sir, but it checks out: Luke Hart found that when he was burnt out, taking a time limited break helped him to reconnect with the game and come back to it with reengaged enthusiasm (Hart (2024)), and likewise Hill (2022) describes that ‘doing nothing’ and instead “tending to your physical needs for sleep, time off, time in nature, or time away from work demands can be the best medicine“ when it comes to repairing burnout.

In order to achieve this zen like mindset of chilling-the-fluff-out, Hill (2022) suggests 3 positive actions:

Practice some self forgiveness and self love - be as supportive to yourself as you would be toward a friend.

Commit to not trying to fix the issue - stop doing all the things you’re frantically trying.

In it’s place, be accepting - it is what it is, and it will pass.

Flip the Script

Sometimes you just need to satiate your desire for some new thing that’s taken your fancy. It doesn’t even have to be a permanent change, even a temporary side-quest can be enough to recover your mojo.

Ciechhanowski (2016) prefers to mix things up by shortening the length of his sessions. He does this engineering each game with a single objective in mind - maybe that objective came from his planning, or maybe it came from asking the players at the start what they wanted to do. The important thing is that it’s something short term achievable rather than some miniature tangled spiders web of elements to put together.

Simply put, once the players have accomplished this, he calls time for the evening and stops.

Alternatively, Arcadian (2008) makes no bones about simply advocating that you play something different when the current game no longer aligns with your values. This doesn’t have to be as drastic as putting something down, mid-campaign for good - rather a temporary palette cleanser game could be just the ticket.

Maybe think of it as an opportunity to try one of those TTRPGs you kickstarted last year!

However, if flipping the system isn’t an option, you might want to try running the next session to a different beat, if your games are normally combat heavy, why not run an investigation? If you normally deliver your players with a gripping political intrigue, maybe it’s about time that you unleashed some horror? Hart (2024)

Of course, what any one game can handle is limited, and if you are running D&D, I’d never suggest trying to squeeze a horror session out of it!

Finally, I wrote a piece a few months ago that advocates for running serialised episodic adventures. You know, like TV shows in the 90s. Every episode largely stands alone, sometimes with a central thread tying them all together. The beauty of this is that it makes your campaign very modular, and all the more easy to insert new modules in as you see fit.

Reconnect With What You Love

We’ve all got a favourite element of game mastering, that element that drew us aboard in the first place. Find it, dive back into it. Maybe it’s world building? Maybe it’s drawing maps, or designing a pantheon of Gods. Hell, maybe it’s the thrill of improvising everything up at the table, and living on the edge! Hart (2024) suggests spending some time in this zone and allowing it to reignite your enthusiasm.

When you’ve filled your cup again, you can step once more into the breach!

Let Players Ease The Pressure

If you’re simply finding it all a bit too much responsibility, talk to your players. Let that bunch of pirates shoulder some of the work! The most glaring example here could be to let one of them run a game whilst you play for a while, but we don’t have to go that far. Perhaps you could allocate Ian with the job of doing session write-ups, whilst Chris might be more suited to organising everyone’s availability for the next session.

Additionally, direct your players to up their game. Players shouldn’t be resting on their laurels, expecting you to spoon feed the entirety of the game to them at the table. Rather, let them do some imagining too, why not ask Shaun to describe the Goblins kitchen to everyone - it’ll be fine, just roll with whatever he comes up with, and don’t forget that you’ve got Paige on hand to keep the lore straight.

Whatever you do, just don’t put Alan in charge of the session recap though, that dude can’t even remember what he had for breakfast!

Stimulate Creativity Through Novelty

Davies (2025) highlights that the brain’s capacity for creativity does not happen in isolation from the body or environment. If you’re in a bit of a slump, you should consider the following:

Get off your butt, have a shower, and get some air outside! Studies show that at least 15 minutes of proper physical activity boosts creativity and can help you find novel solutions to problems.

Surprise yourself! Do something you wouldn’t normally do, maybe whack on ‘Wannabe’ by the Spice Girls, learn the words and dance around the house like a teenager from 1996. Doing so can “stimulate curiosity and [give you] healthy dopamine doses“ improving your mood and putting you back into a creative mindset.

Conclusion

I know, burnout sucks, believe me - as a blog writer, I feel it acutely from time to time, but it’s not a permanent state, and these tips can help. If you want to offload, feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below and I’ll get back to you. Until then, I hope you’re feeling better soon!

Hey, thanks for reading - you’re good people. If you’ve enjoyed this, it’d be great if you could share it on your socials - it really helps me out and costs you nothing! If you’re super into it and want to make sure you catch more of my content, subscribe to my free monthly Mailer of Many Things newsletter - it really makes a huge difference, and helps me keep this thing running! If you’ve still got some time to kill, Perhaps I can persuade you to click through below to another one of my other posts?

Catch you laters, alligators.

References

Many thanks to the following sources for their work on the subject:

*FYI, full dates are written in dd-mm-yyyy because mm-dd-yyyy is bonkers :)

Six Sources of Burnout at Work (2013), by Davies, P. Published in Psychology Today. Accessed 12-01-2026

Move, Connect, and Create to Reverse Burnout (2025), by Davies, J. Published in Psychology Today. Accessed 12-01-2026

When You Aren’t Feeling It (2016), by Ciechanowski, W. Published in Gnome Stew. Accessed 12-01-2026

How to Overcome Dungeon Master Burnout (2024), by Hart, L. Published in The DM Lair. Accessed 12-01-2026

Gamer Burnout – Both GM and Player (2008), by Arcadian, J. Published in Gnome Stew. Accessed 12-01-2026

Doing Nothing Is Doing Something (2022), by Hill, D. Published in Psychology Today. Accessed 12-01-2026

Creative Burnout: Why It Happens and How to Beat It (2025), by Tyler, E . Published in Metricool. Accessed 12-01-2026

The Five Whys Technique (2009), by Serrat, O. Published in ABD Institute. Accessed 14-01-2026

Happy New Year! 2025 Is Over!

Post 52 baby!

By JimmiWazEre

Opinionated tabletop gaming chap who desperately needs to put out this 52nd post.

Well This is an unusual Format…

Ha, yes it is. Look, levelling with you here. I was planning on putting out something more substantial today but life got in the way, that said - I can’t let the year end on 51 posts - that’d be criminal!

So, this is what you’re getting - a stream of conscious from me. I was watching Breaking Bad downstairs with Mrs. WazEre and I told her I’d just be a few minutes. That’s not a lot of time to go into anything substantial really.

I guess I’ll give you a quick peep at ones coming up in January: I’ve got the final part in the dice mechanic series coming along nicely. I’ve also been working on a kinda academic piece on GM burnout. Outside of blogging, I’m going to be running Chariot of the Gods again for a new audience, and with the new Alien Evolved Edition rules. At the weekend I have a friend from Manchester coming over - We’re going to have a stab at designing a Pirate themed board game - looking forward to giving you more details on that later.

On top of that, I need to turn my attention to my hobby room. It’s a bit of a mess frankly, and I’ve got a woodworking project I need to finish. I’m building a set of wall mounted shelving which will also double up as a new desk. The overall effect is going to mean I’ll have significantly less stuff ‘out’ or on the floor, and more stuff put away up on display. That’s a pleasing thought indeed.

This’ll do I think, I’m definitely phoning it in on this one, but if you’ve bothered to read this far, and if you’ve followed DoMT this year, I want to sincerely thank you from the bottom of my salty heart. It’s been a journey!

Peace out.

JimmiWazEre 2025